Clean Code 2 edition: Go example Appendix

This is an appendix to the Video Store Go example in Robert C. Martin’s second edition of Clean Code.

This appendix aims to extend the example with some Go idioms that can improve the example.

Good practices references

I’m basing the suggestions in this appendix on official references and my experience in practical Go. Here are a couple official references for the Go good practices:

Table of Contents

Package name

Single-word package names are preferred in Go.

Good package names are short and clear. They are lower case, with no

under_scoresormixedCaps. They are often simple nouns, such as:

time(provides functionality for measuring and displaying time)list(implements a doubly linked list)http(provides HTTP client and server implementations)The style of names typical of another language might not be idiomatic in a Go program. Here are two examples of names that might be good style in other languages but do not fit well in Go:

computeServiceClientpriority_queue

From my experience, some code bases use snake cases for package names, but it’s not a common practice in Go.

For the provided example, I would use store instead of GoVideoStore.

For more complex projects (like Wild Workouts), where you want to keep an entity per package, you can use rental.

Tip

Remember: encapsulation in Go is package-wise. Keeping multiple loosely related entities in one package may lead to accidental coupling.

File names

No official guidance on file names exists, but single-word file names are preferred.

If a two-word file name is needed (for example, rental_statement_test.go), you can use a snake case.

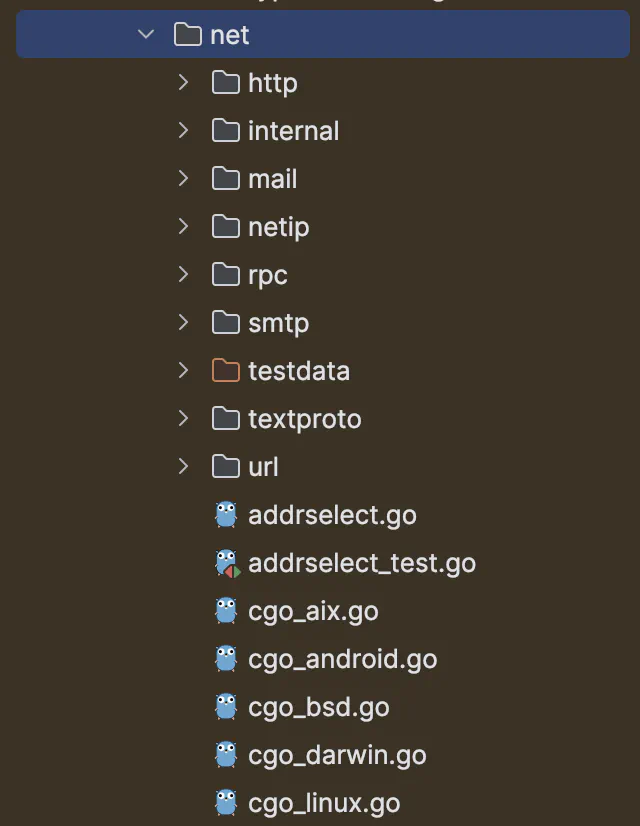

The Go standard library can give us some guidance on the convention used.

Projects usually follow the same format as the standard library. Camel case or Pascal case is not used in Go file names.

Struct receivers

In Go, we are using single-letter struct receivers in struct methods.

Go Code Review comments say:

The name of a method’s receiver should be a reflection of its identity; often, a one or two-letter abbreviation of its type suffices (such as

"c"or"cl"for"Client").

So, for example:

-func (rental Rental) determineAmount() float64 {

- return rental.rentalType.determineAmount(rental.daysRented)

+func (r Rental) determineAmount() float64 {

+ return r.rentalType.determineAmount(r.daysRented)

}

It may sound like reduced readability for people from other languages, but it’s not in practice. After some time, it’s natural as you know what structure you are working on, so it’s not a problem.

Getters

In Go, we are not prefixing getters with “Get”.

Go doesn’t provide automatic support for getters and setters. There’s nothing wrong with providing getters and setters yourself, and it’s often appropriate to do so, but it’s neither idiomatic nor necessary to put

Getinto the getter’s name. If you have a field called owner (lower case, unexported), the getter method should be calledOwner(upper case, exported), notGetOwner.

So, for example, instead of getTitle(), we should use title():

-func (rental Rental) getTitle() string {

- return rental.movie.title

+func (r Rental) title() string {

+ return r.movie.title

}

Black-box testing

Currently, the tests are in the same package as the tested code.

It’s a good practice to use a black-box testing strategy. It helps us to focus on testing the public API of the package, not the implementation details.

Go has native support for black-box testing.

To use black-box testing, you should prefix the test package name with the _test prefix.

It will allow you to use only public methods from the tested package.

+++ b/rental_statement_test.go

@@ -1,33 +1,35 @@

-package GoVideoStore

+package store_test

import (

"testing"

+

+ store "github.com/unclebob/GoVideoStore"

)

Public API

Switching to black-box testing helped us to distill the public API of the package and find all the methods that should be public. For example:

-func (r RentalTypeFactoryImpl) make(typeName string) RentalType {

+func (r RentalTypeFactoryImpl) Make(typeName string) RentalType {

switch typeName {

case "childrens":

- return ChildrensRental{}

+ return childrensRental{}

case "new release":

- return NewReleaseRental{}

+ return newReleaseRental{}

case "regular":

- return RegularRental{}

+ return regularRental{}

}

return nil

Tests shows us also that we can make public surface of the package smaller and some types private:

-type ChildrensRental struct{}

+type childrensRental struct{}

-type NewReleaseRental struct{}

+type newReleaseRental struct{}

-type RegularRental struct{}

+type regularRental struct{}

Missing error handling and validation

We should add error handling and validation to the constructors to make our code more robust.

It’s how it could look like for NewMovie:

func NewMovie(title string) (*Movie, error) {

if title == "" {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("title cannot be empty")

}

return &Movie{title: title}, nil

}

If we need to do more complex validation with multiple validation rules, we can use the errors package to

join multiple errors into one:

func NewRental(movie *Movie, rentalType RentalType, daysRented int) (*Rental, error) {

var err error

if movie == nil {

err = errors.Join(err, errors.New("movie cannot be nil"))

}

if rentalType == nil {

err = errors.Join(err, errors.New("rentalType cannot be nil"))

}

if daysRented < 0 {

err = errors.Join(err, errors.New("daysRented cannot be negative"))

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &Rental{

movie: movie,

rentalType: rentalType,

daysRented: daysRented,

}, nil

}

Thanks to that, we won’t receive only the first error but all of them.