4 practical principles of high-quality database integration tests in Go

Did you ever hear about a project where changes were tested on customers you don’t like or countries that aren’t profitable? Or even worse: did you work on such a project?

It’s not enough to say that it’s unfair and unprofessional. It’s also hard to develop anything new because you’re afraid to make any change in your codebase.

In the 2019 HackerRank Developer Skills Report, Professional growth & learning was marked as the most important factor when looking for a new job. Do you think you can learn anything and grow when you test your application this way?

It all leads to frustration and burnout.

To develop your application easily and with confidence, you need a set of tests on multiple levels. In this article, I will cover practical examples of implementing high-quality database integration tests. I will also cover basic Go testing techniques, like test tables, assert functions, parallel execution, and black-box testing.

What does it actually mean for test quality to be high?

4 principles of high-quality tests

I prepared 4 rules that we need to pass to say that our integration test quality is high.

1. Fast

Good tests need to be fast. There is no compromise here.

Everybody hates long-running tests. Think about your teammates’ time and mental health when they’re waiting for test results, both in CI and locally. It’s terrifying.

When you wait for a long time, you’ll likely start doing something else in the meantime. After the CI passes (hopefully), you’ll need to switch back to this task. Context switching is one of the biggest productivity killers. It’s exhausting for our brains. We are not robots.

I know that some companies still have tests that run for 24 hours. We don’t want to follow this approach. 😉 You should be able to run your tests locally in less than 1 minute, ideally in less than 10s. I know that sometimes this requires a time investment. It’s an investment with an excellent ROI (Return on Investment)! You can quickly check your changes, and deployment times are much shorter too.

From my experience, it’s always worth finding quick wins that reduce test execution time the most. The Pareto principle (80/20 rule) works here perfectly!

2. Testing enough scenarios on all levels

I hope you already know that 100% test coverage is not the best idea (unless it’s a simple/critical library).

It’s always a good idea to ask yourself the question “how easily can it break?”. It’s even more worth asking this question if the test you’re implementing starts to look exactly like the function you’re testing. At the end of the day, we’re not writing tests because tests are nice: they should save our ass!

From my experience, coverage like 70-80% is a pretty good result in Go.

It’s also not the best idea to cover everything with component or end-to-end tests. First, you won’t be able to do that because of the inability to simulate some error scenarios, like rollbacks on the repository. Second, it will break the first rule: these tests will be slow.

Tests on several layers should also overlap, so we will know that integration is done correctly.

You may think that solution for that is simple: the test pyramid! And that’s true…sometimes. Especially in applications that handle a lot of operations based on writes.

But what about applications that aggregate data from multiple services and expose it via API? They have no complex logic for saving the data. Most of the code is probably related to database operations. In this case, we should use a reversed test pyramid (it actually looks more like a Christmas tree). When a big part of our application is connected to infrastructure (for example, a database), it’s hard to cover a lot of functionality with unit tests.

3. Tests need to be robust and deterministic

Do you know that feeling when you’re doing some urgent fix, tests are passing locally, you push changes to the repository and… after 20 minutes they fail in the CI? It’s incredibly frustrating. It also discourages us from adding new tests and decreases our trust in them.

You should fix that issue as fast as you can. The Broken windows theory is really valid here.

4. You should be able to execute most of the tests locally

Tests that you run locally should give you enough confidence that the feature you developed or refactored is still working. E2E tests should just double-check if everything is integrated correctly.

You’ll also have much more confidence when contracts between services are robust because of using gRPC, protobuf, or OpenAPI.

This is a good reason to cover as much as we can at lower levels (starting with the lowest): unit, integration, and component tests. Only then E2E.

Implementation

We have some common theoretical ground. But nobody pays us for being masters of programming theory. Let’s go to some practical examples that you can implement in your project.

Let’s start with the repository pattern that I described in the previous article. You don’t need to read the rest of the articles in the series, but it’s a good idea to check at least the previous one. It will make it much clearer how our repository implementation works.

Note

This is not just another article with random code snippets.

This post is part of a bigger series where we show how to build Go applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. We are doing it by sharing proven techniques based on many experiments we did with teams we lead and scientific research.

You can learn these patterns by building with us a fully functional example Go web application – Wild Workouts.

We did one thing differently – we included some subtle issues to the initial Wild Workouts implementation. Have we lost our minds to do that? Not yet. 😉 These issues are common for many Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and stop adding new features.

It’s one of the essential skills of a senior or lead developer; you always need to keep long-term implications in mind.

We will fix them by refactoring Wild Workouts. In that way, you will quickly understand the techniques we share.

Do you know that feeling after reading an article about some technique and trying implement it only to be blocked by some issues skipped in the guide? Cutting these details makes articles shorter and increases page views, but this is not our goal. Our goal is to create content that provides enough know-how to apply presented techniques. If you did not read previous articles from the series yet, we highly recommend doing that.

We believe that in some areas, there are no shortcuts. If you want to build complex applications in a fast and efficient way, you need to spend some time learning that. If it was simple, we wouldn’t have large amounts of scary legacy code.

Here’s the full list of 14 articles released so far.

The full source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. Don’t forget to leave a star for our project! ⭐

The way we interact with our database is defined by the hour.Repository interface.

It assumes that our repository implementation is simple.

All complex logic is handled by the domain part of our application.

It should just save the data without any validations, etc.

One of the significant advantages of this approach is the simplification of the repository and test implementation.

In the previous article, I prepared three different database implementations: MySQL, Firebase, and in-memory. We will test all of them. They are fully compatible, so we can have just one test suite.

package hour

type Repository interface {

GetOrCreateHour(ctx context.Context, hourTime time.Time) (*Hour, error)

UpdateHour(

ctx context.Context,

hourTime time.Time,

updateFn func(h *Hour) (*Hour, error),

) error

}

Because of multiple repository implementations, in our tests we iterate through a list of them.

Note

It’s actually a pretty similar pattern to how we implemented tests in Watermill.

All Pub/Sub implementations are passing the same test suite.

All tests that we write will be black-box tests.

In other words, we will only cover public functions with tests.

To ensure that, all our test packages have the _test suffix.

This forces us to use only the public interface of the package.

It will pay back in the future with much more stable tests that are not affected by any internal changes.

If you can’t write good black-box tests, you should consider if your public APIs are well designed.

All our repository tests are executed in parallel. Thanks to that, they take less than 200ms.

After adding multiple test cases, this time should not increase significantly.

package main_test

// ...

func TestRepository(t *testing.T) {

rand.Seed(time.Now().UTC().UnixNano())

repositories := createRepositories(t)

for i := range repositories {

// When you are looping over the slice and later using iterated value in goroutine (here because of t.Parallel()),

// you need to always create variable scoped in loop body!

// More info here: https://github.com/golang/go/wiki/CommonMistakes#using-goroutines-on-loop-iterator-variables

r := repositories[i]

t.Run(r.Name, func(t *testing.T) {

// It's always a good idea to build all non-unit tests to be able to work in parallel.

// Thanks to that, your tests will be always fast and you will not be afraid to add more tests because of slowdown.

t.Parallel()

t.Run("testUpdateHour", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

testUpdateHour(t, r.Repository)

})

t.Run("testUpdateHour_parallel", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

testUpdateHour_parallel(t, r.Repository)

})

t.Run("testHourRepository_update_existing", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

testHourRepository_update_existing(t, r.Repository)

})

t.Run("testUpdateHour_rollback", func(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

testUpdateHour_rollback(t, r.Repository)

})

})

}

}

When we have multiple tests where we pass the same input and check the same output, it’s a good idea to use a technique known as test table. The idea is simple: define a slice of inputs and expected outputs, then iterate over it to execute tests.

func testUpdateHour(t *testing.T, repository hour.Repository) {

t.Helper()

ctx := context.Background()

testCases := []struct {

Name string

CreateHour func(*testing.T) *hour.Hour

}{

{

Name: "available_hour",

CreateHour: func(t *testing.T) *hour.Hour {

return newValidAvailableHour(t)

},

},

{

Name: "not_available_hour",

CreateHour: func(t *testing.T) *hour.Hour {

h := newValidAvailableHour(t)

require.NoError(t, h.MakeNotAvailable())

return h

},

},

{

Name: "hour_with_training",

CreateHour: func(t *testing.T) *hour.Hour {

h := newValidAvailableHour(t)

require.NoError(t, h.ScheduleTraining())

return h

},

},

}

for _, tc := range testCases {

t.Run(tc.Name, func(t *testing.T) {

newHour := tc.CreateHour(t)

err := repository.UpdateHour(ctx, newHour.Time(), func(_ *hour.Hour) (*hour.Hour, error) {

// UpdateHour provides us existing/new *hour.Hour,

// but we are ignoring this hour and persisting result of `CreateHour`

// we can assert this hour later in assertHourInRepository

return newHour, nil

})

require.NoError(t, err)

assertHourInRepository(ctx, t, repository, newHour)

})

}

You can see that we used the popular github.com/stretchr/testify library.

It significantly reduces boilerplate in tests by providing multiple helpers for asserts.

Note

require.NoError()

When assert.NoError assert fails, test execution is not interrupted.

It’s worth mentioning that asserts from the require package stop execution of the test when they fail.

Because of that, it’s often a good idea to use require for checking errors.

In many cases, if some operation fails, it doesn’t make sense to check anything later.

When we assert multiple values, assert is a better choice because you will receive more context.

If we have more specific data to assert, it’s always a good idea to add some helpers. It removes a lot of duplication and improves test readability!

func assertHourInRepository(ctx context.Context, t *testing.T, repo hour.Repository, hour *hour.Hour) {

require.NotNil(t, hour)

hourFromRepo, err := repo.GetOrCreateHour(ctx, hour.Time())

require.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, hour, hourFromRepo)

}

Testing transactions

Mistakes taught me that I should not trust myself when implementing complex code. Sometimes we don’t understand the documentation or just introduce some stupid mistake. You can gain confidence in two ways:

- TDD - let’s start with a test that will check if the transaction is working properly.

- Let’s start with the implementation and add tests later.

func testUpdateHour_rollback(t *testing.T, repository hour.Repository) {

t.Helper()

ctx := context.Background()

hourTime := newValidHourTime()

err := repository.UpdateHour(ctx, hourTime, func(h *hour.Hour) (*hour.Hour, error) {

require.NoError(t, h.MakeAvailable())

return h, nil

})

err = repository.UpdateHour(ctx, hourTime, func(h *hour.Hour) (*hour.Hour, error) {

assert.True(t, h.IsAvailable())

require.NoError(t, h.MakeNotAvailable())

return h, errors.New("something went wrong")

})

require.Error(t, err)

persistedHour, err := repository.GetOrCreateHour(ctx, hourTime)

require.NoError(t, err)

assert.True(t, persistedHour.IsAvailable(), "availability change was persisted, not rolled back")

}

When I’m not using TDD, I try to be paranoid about whether the test implementation is valid.

To be more confident, I use a technique that I call test sabotage.

The method is simple: break the implementation that we’re testing and see if anything fails.

func (m MySQLHourRepository) finishTransaction(err error, tx *sqlx.Tx) error {

- if err != nil {

- if rollbackErr := tx.Rollback(); rollbackErr != nil {

- return multierr.Combine(err, rollbackErr)

- }

-

- return err

- } else {

- if commitErr := tx.Commit(); commitErr != nil {

- return errors.Wrap(err, "failed to commit tx")

- }

-

- return nil

+ if commitErr := tx.Commit(); commitErr != nil {

+ return errors.Wrap(err, "failed to commit tx")

}

+

+ return nil

}

If your tests are passing after a change like that, I have bad news…

Testing database race conditions

Our applications don’t work in a void. It can always happen that multiple clients try to do the same operation, and only one can win!

In our case, the typical scenario is when two clients try to schedule a training at the same time. We can have only one training scheduled in one hour.

This constraint is achieved by optimistic locking (described in the previous article) and domain constraints (described two articles ago).

Let’s verify if it’s possible to schedule one hour more than once. The idea is simple: create 20 goroutines, release them all at once, and try to schedule training. We expect exactly one worker to succeed.

func testUpdateHour_parallel(t *testing.T, repository hour.Repository) {

// ...

workersCount := 20

workersDone := sync.WaitGroup{}

workersDone.Add(workersCount)

// closing startWorkers will unblock all workers at once,

// thanks to that it will be more likely to have race condition

startWorkers := make(chan struct{})

// if training was successfully scheduled, number of the worker is sent to this channel

trainingsScheduled := make(chan int, workersCount)

// we are trying to do race condition, in practice only one worker should be able to finish transaction

for worker := 0; worker < workersCount; worker++ {

workerNum := worker

go func() {

defer workersDone.Done()

<-startWorkers

schedulingTraining := false

err := repository.UpdateHour(ctx, hourTime, func(h *hour.Hour) (*hour.Hour, error) {

// training is already scheduled, nothing to do there

if h.HasTrainingScheduled() {

return h, nil

}

// training is not scheduled yet, so let's try to do that

if err := h.ScheduleTraining(); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

schedulingTraining = true

return h, nil

})

if schedulingTraining && err == nil {

// training is only scheduled if UpdateHour didn't return an error

trainingsScheduled <- workerNum

}

}()

}

close(startWorkers)

// we are waiting, when all workers did the job

workersDone.Wait()

close(trainingsScheduled)

var workersScheduledTraining []int

for workerNum := range trainingsScheduled {

workersScheduledTraining = append(workersScheduledTraining, workerNum)

}

assert.Len(t, workersScheduledTraining, 1, "only one worker should schedule training")

}

This is also a good example of use cases that are easier to test at the integration test level, not at acceptance or E2E level. Tests like this as E2E would be really heavy, and you would need more workers to ensure they execute transactions simultaneously.

Making tests fast

If your tests can’t be executed in parallel, they will be slow. Even on the best machine.

Is putting t.Parallel() enough?

Well, we need to ensure that our tests are independent.

In our case, if two tests tried to edit the same hour, they could fail randomly.

This is a highly undesirable situation.

To achieve that, I created the newValidHourTime() function that provides a random hour unique to the current test run.

In most applications, generating a unique UUID for your entities may be enough.

In some situations, it may be less obvious but still not impossible. I encourage you to spend some time finding the solution. Please treat it as an investment in your and your teammates’ mental health 😉.

// usedHours is storing hours used during the test,

// to ensure that within one test run we are not using the same hour

// (it should be not a problem between test runs)

var usedHours = sync.Map{}

func newValidHourTime() time.Time {

for {

minTime := time.Now().AddDate(0, 0, 1)

minTimestamp := minTime.Unix()

maxTimestamp := minTime.AddDate(0, 0, testHourFactory.Config().MaxWeeksInTheFutureToSet*7).Unix()

t := time.Unix(rand.Int63n(maxTimestamp-minTimestamp)+minTimestamp, 0).Truncate(time.Hour).Local()

_, alreadyUsed := usedHours.LoadOrStore(t.Unix(), true)

if !alreadyUsed {

return t

}

}

}

Another good thing about making our tests independent is that there’s no need for data cleanup. In my experience, doing data cleanup is always messy because:

- when it doesn’t work correctly, it creates hard-to-debug issues in tests,

- it makes tests slower,

- it adds overhead to development (you need to remember to update the cleanup function),

- it may make running tests in parallel harder.

It may also happen that we’re not able to run tests in parallel. Two common examples are:

- pagination: if you iterate over pages, other tests can insert something in-between and move “items” in the pages.

- global counters: like with pagination, other tests may affect the counter in an unexpected way.

In that case, it’s worth keeping these tests as short as we can.

Please, don’t use sleep in tests!

The last tip about what makes tests flaky and slow: putting the sleep function in them. Please, don’t!

It’s much better to synchronize your tests with channels or sync.WaitGroup{}.

They are faster and more stable that way.

If you really need to wait for something, it’s better to use assert.Eventually instead of a sleep.

Note

Eventually asserts that given condition will be met in waitFor time, periodically checking target function each tick.

assert.Eventually(

t,

func() bool { return true }, // condition

time.Second, // waitFor

10*time.Millisecond, // tick

)

Running

Now that our tests are implemented, it’s time to run them!

Before that, we need to start our container with Firebase and MySQL using docker-compose up.

I prepared a make test command that runs tests in a consistent way (for example, with the -race flag).

It can also be used in CI.

$ make test

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/auth []

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/client [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/genproto/trainer [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/genproto/users [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/logs [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/server [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/common/server/httperr [no test files]

ok github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/trainer 0.172s

ok github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/trainer/domain/hour 0.031s

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/trainings [no test files]

? github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/internal/users [no test files]

Running one test and passing custom params

If you would like to pass some extra params, to have a verbose output (-v) or execute exact test (-run), you can pass it after make test --.

$ make test -- -v -run ^TestRepository/memory/testUpdateHour$

--- PASS: TestRepository (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestRepository/memory (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestRepository/memory/testUpdateHour (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestRepository/memory/testUpdateHour/available_hour (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestRepository/memory/testUpdateHour/not_available_hour (0.00s)

--- PASS: TestRepository/memory/testUpdateHour/hour_with_training (0.00s)

PASS

If you are interested in how it is implemented, I’d recommend you check my Makefile magic :man_mage:.

Debugging

Sometimes our tests fail in an unclear way. In that case, it’s useful to be able to easily check what data is in our database.

For SQL databases, my first choice for that is mycli for MySQL and pgcli for PostgreSQL.

I’ve added a make mycli command to the Makefile, so you don’t need to pass credentials all the time.

$ make mycli

mysql user@localhost:db> SELECT * from `hours`;

+---------------------+--------------------+

| hour | availability |

|---------------------+--------------------|

| 2020-08-31 15:00:00 | available |

| 2020-09-13 19:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2022-07-19 19:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2023-03-19 14:00:00 | available |

| 2023-08-05 03:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2024-01-17 07:00:00 | not_available |

| 2024-02-07 15:00:00 | available |

| 2024-05-07 18:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2024-05-22 09:00:00 | available |

| 2025-03-04 15:00:00 | available |

| 2025-04-15 08:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2026-05-22 09:00:00 | training_scheduled |

| 2028-01-24 18:00:00 | not_available |

| 2028-07-09 00:00:00 | not_available |

| 2029-09-23 15:00:00 | training_scheduled |

+---------------------+--------------------+

15 rows in set

Time: 0.025s

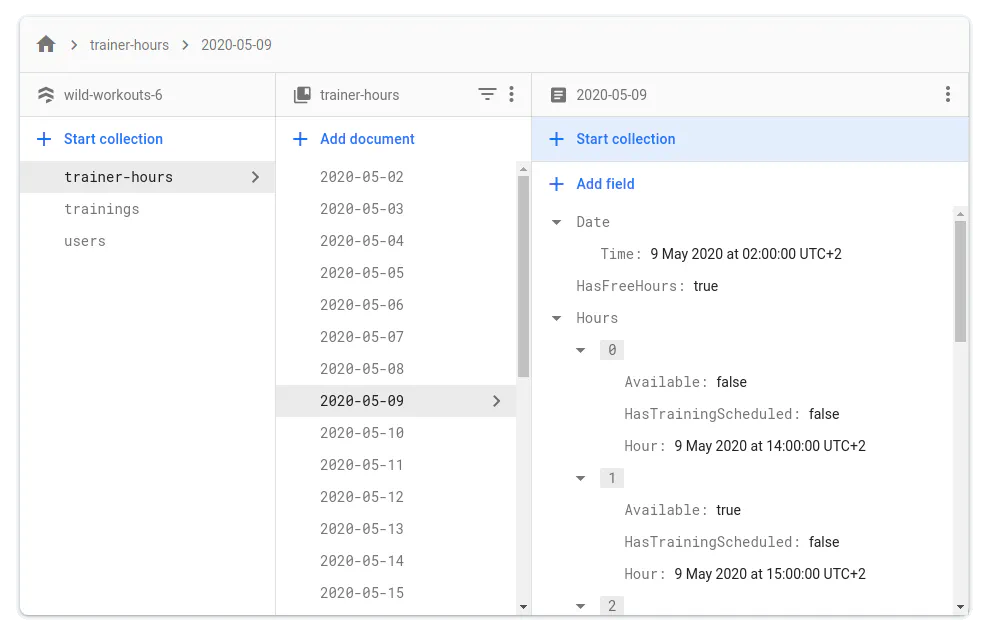

For Firestore, the emulator is exposing the UI at localhost:4000/firestore.

First step for having a well-tested application

The biggest gap we currently have is a lack of tests at the component and E2E level. Also, a big part of the application is not tested at all. We will fix that in the next articles. We will also cover some topics that we skipped this time.

But before that, we have one topic that we need to cover first: Clean/Hexagonal architecture! This approach will help us organize our application and make future refactoring and features easier to implement.

Just to remind, the entire source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. You can run it locally and deploy to Google Cloud with one command.

Did you like this article and haven’t had a chance to read the previous ones? There are 14 more articles to check!

And that’s all for today. See you soon! 🙂