You should not build your own authentication

We intentionally built the current version of the application to make it hard to maintain and develop in the future. In a subtle way. 😉 In the next article, we will start the refactoring process. We will show you how subtle issues and shortcuts can become a problem in the long term. Even adding a new feature now may not be as easy as developing greenfield features (even if the application is still pretty new).

But before that, we have one important topic to cover: authentication. This is the part of the application that will not need refactoring. 😉

You shouldn’t reinvent the wheel

(I hope that) you are not creating a programming language and a framework for every project you work on. Even if you do that, besides losing a lot of time, it’s not harmful. That’s not the case for authentication. Why?

Let’s imagine that you are working in a company implementing a cryptocurrency exchange. At the beginning of the project, you decided to build your own authentication mechanism. The first reason is your boss, who doesn’t trust external authentication providers. The second reason is that you believe it should be simple.

“You did it many times” – this is what strange voices in your head repeat every time.

Have you seen the Mayday / Air Crash Investigation documentary TV series? In the Polish edition, every episode starts with something like: “Catastrophes are not a matter of coincidence, but a series of unfortunate events.” In programming, this statement is surprisingly true.

In our hypothetical project, your company decided to introduce a service account that could move funds between any account. Even from a wallet that, in theory, should be offline. Of course, only temporarily. 😆 That doesn’t sound like a good idea, but it simplified customer support from the very beginning.

With time, everyone forgot about this feature. Until one day, when hackers found a bug in the authentication mechanism that allowed them to hijack any account on our exchange. Including the service account.

Our boss and coworkers were less happy than the hackers because they lost all the money. The problem wouldn’t be so big if we’d lost “only” the company’s money. In this case, we also lost all our customers’ money. 😉

This example may sound extreme and unlikely to happen. Is it a rare scenario? The OWASP Top Ten report lists Broken Authentication in second place!

- Broken Authentication. Application functions related to authentication and session management are often implemented incorrectly, allowing attackers to compromise passwords, keys, or session tokens, or to exploit other implementation flaws to assume other users’ identities temporarily or permanently.

You may say: “My company is just selling toasters! Why should I care?” I’m pretty sure you still care about your company’s image. The reputational damage after an incident caused by hackers hijacking your customers’ accounts is always embarrassing.

Do you still feel that you can implement perfect authentication? Even giants with hundreds of researchers and developers working just on authentication are unable to do that. In March 2020, a researcher found a Facebook vulnerability that could allow hijacking anyone’s Facebook account. Just a few months later, a bug in Apple Sign In allowed full account takeover of user accounts on third-party applications.

If you’re still not convinced, consider saving your time. I’m sure your customers will be much happier to receive a long-awaited feature than fancy, custom authentication. 😉

Using Firebase authentication

Many solutions can be used for implementing authentication.

The Wild Workouts example application that we created for this article series is now hosted on Firebase hosting. We will use Firebase Authentication. There is one significant advantage of this solution: it works almost entirely out of the box, both on the backend and frontend. Using an external identity provider shouldn’t introduce significant vendor lock-in, as long as you design your integration to be easily switchable. We’ll cover how to do that in a future article. 😉

Note

Authentication recommendation in 2026

As of 2026, we recommend using passwordless login combined with SSO (Google, Facebook, GitHub) for most applications. This approach offers the best balance of security and user experience: no passwords to remember or leak, and users sign in with accounts they already have.

You can easily switch authentication providers when you use an Identity Provider (IDP) correctly. Design your system so the IDP handles only authentication, while your application manages authorization and user data separately. This keeps your core business logic decoupled from the IDP, making future migrations straightforward.

Note

This is not just another article with random code snippets.

This post is part of a bigger series where we show how to build Go applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. We are doing it by sharing proven techniques based on many experiments we did with teams we lead and scientific research.

You can learn these patterns by building with us a fully functional example Go web application – Wild Workouts.

We did one thing differently – we included some subtle issues to the initial Wild Workouts implementation. Have we lost our minds to do that? Not yet. 😉 These issues are common for many Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and stop adding new features.

It’s one of the essential skills of a senior or lead developer; you always need to keep long-term implications in mind.

We will fix them by refactoring Wild Workouts. In that way, you will quickly understand the techniques we share.

Do you know that feeling after reading an article about some technique and trying implement it only to be blocked by some issues skipped in the guide? Cutting these details makes articles shorter and increases page views, but this is not our goal. Our goal is to create content that provides enough know-how to apply presented techniques. If you did not read previous articles from the series yet, we highly recommend doing that.

We believe that in some areas, there are no shortcuts. If you want to build complex applications in a fast and efficient way, you need to spend some time learning that. If it was simple, we wouldn’t have large amounts of scary legacy code.

Here’s the full list of 14 articles released so far.

The full source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. Don’t forget to leave a star for our project! ⭐

Note

Deployment of the project is described in detail in the A complete Terraform setup of a serverless application on Google Cloud Run and Firebase article.

In the first article you can find deployment tl;dr at the end.

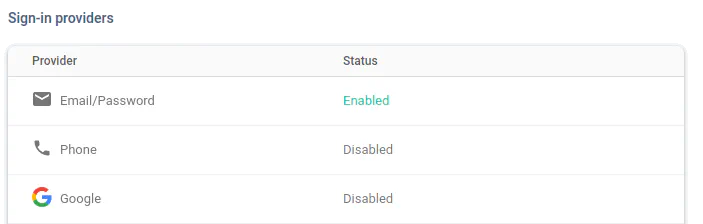

During the setup, don't forget about enabling Email/Password Sign-in provider in Authentication / Sign-in method tab in the [Firebase Console](https://console.firebase.google.com/project/_/authentication/providers)!

Frontend

The first thing that we need to do is the initialization of Firebase SDK.

Next, in the form on the main page, we call the loginUser function.

This function calls Auth.login, Auth.waitForAuthReady, and Auth.getJwtToken.

The result is set to OpenAPI-generated clients by setApiClientsAuth.

// ...

export function loginUser(login, password) {

return Auth.login(login, password)

.then(function () {

return Auth.waitForAuthReady()

})

.then(function () {

return Auth.getJwtToken(false)

})

.then(token => {

setApiClientsAuth(token)

})

// ...

Auth is a class with two implementations: Firebase and mock.

We will go through the mock implementation later. Let’s focus on Firebase now.

To log in, we need to call firebase.auth().signInWithEmailAndPassword. If everything is fine, auth().currentUser.getIdToken returns our JWT token.

class FirebaseAuth {

login(login, password) {

return firebase.auth().signInWithEmailAndPassword(login, password)

}

waitForAuthReady() {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

firebase

.auth()

.onAuthStateChanged(function () {

resolve()

});

})

}

getJwtToken(required) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

if (!firebase.auth().currentUser) {

if (required) {

reject('no user found')

} else {

resolve(null)

}

return

}

firebase.auth().currentUser.getIdToken(false)

.then(function (idToken) {

resolve(idToken)

})

.catch(function (error) {

reject(error)

});

})

}

Note

Firebase also provides out of the box support for logging in with most popular OAuth providers like Facebook, Gmail, or GitHub.

Next, we need to set authentications['bearerAuth'].accessToken of OpenAPI-generated clients to the JWT token received from Auth.getJwtToken(false).

Once we set this token on the OpenAPI clients, voila! All our requests are now authenticated.

export function setApiClientsAuth(idToken) {

usersClient.authentications['bearerAuth'].accessToken = idToken

trainerClient.authentications['bearerAuth'].accessToken = idToken

trainingsClient.authentications['bearerAuth'].accessToken = idToken

}

Note

If you are creating your own OpenAPI spec, it will not work without proper authentication definition. In Wild Workouts’ OpenAPI spec it’s already done.

If you would like to know more, I recommend checking the Firebase Auth API reference.

Backend

The last part is using this authentication in our HTTP server. I created a simple HTTP middleware that will do this for us.

This middleware does three things:

- Get token from HTTP header

- Verify token with Firebase auth client

- Save user data in credentials

package auth

import (

"context"

"net/http"

"strings"

"firebase.google.com/go/auth"

"github.com/pkg/errors"

"github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/pkg/internal/server/httperr"

)

type FirebaseHttpMiddleware struct {

AuthClient *auth.Client

}

func (a FirebaseHttpMiddleware) Middleware(next http.Handler) http.Handler {

return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

bearerToken := a.tokenFromHeader(r)

if bearerToken == "" {

httperr.Unauthorised("empty-bearer-token", nil, w, r)

return

}

token, err := a.AuthClient.VerifyIDToken(ctx, bearerToken)

if err != nil {

httperr.Unauthorised("unable-to-verify-jwt", err, w, r)

return

}

// it's always a good idea to use custom type as context value (in this case ctxKey)

// because nobody from the outside of the package will be able to override/read this value

ctx = context.WithValue(ctx, userContextKey, User{

UUID: token.UID,

Email: token.Claims["email"].(string),

Role: token.Claims["role"].(string),

DisplayName: token.Claims["name"].(string),

})

r = r.WithContext(ctx)

next.ServeHTTP(w, r)

})

}

type ctxKey int

const (

userContextKey ctxKey = iota

)

// ...

func UserFromCtx(ctx context.Context) (User, error) {

u, ok := ctx.Value(userContextKey).(User)

if ok {

return u, nil

}

return User{}, NoUserInContextError

}

User data can now be accessed in every HTTP request by using auth.UserFromCtx function.

func (h HttpServer) GetTrainings(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user, err := auth.UserFromCtx(r.Context())

if err != nil {

httperr.Unauthorised("no-user-found", err, w, r)

return

}

// ...

We can also limit access to some resources based on the user role.

func (h HttpServer) MakeHourAvailable(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user, err := auth.UserFromCtx(r.Context())

if err != nil {

httperr.Unauthorised("no-user-found", err, w, r)

return

}

if user.Role != "trainer" {

httperr.Unauthorised("invalid-role", nil, w, r)

return

}

Adding users

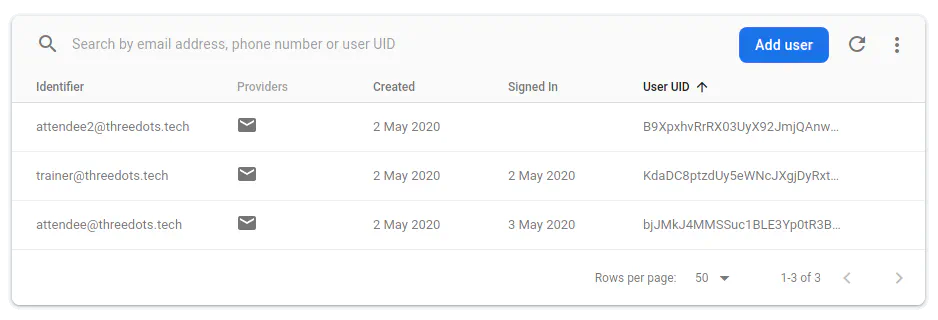

In our case, we add users during the start of the users service. You can also add them from the Firebase UI.

Unfortunately, via the UI you cannot set all required data, like claims: you need to do it via API.

config := &firebase.Config{ProjectID: os.Getenv("GCP_PROJECT")}

firebaseApp, err := firebase.NewApp(context.Background(), config, opts...)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

authClient, err := firebaseApp.Auth(context.Background())

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// ...

for _, user := range usersToCreate {

userToCreate := (&auth.UserToCreate{}).

Email(user.Email).

Password("123456").

DisplayName(user.DisplayName)

createdUser, err := authClient.CreateUser(context.Background(), userToCreate)

// ...

err = authClient.SetCustomUserClaims(context.Background(), createdUser.UID, map[string]interface{}{

"role": user.Role,

})

// ...

Mock Authentication for local dev

Note

Update (2026): Since this article was written, Firebase has released the Authentication Emulator as part of the Local Emulator Suite. You can now run Firebase Authentication locally without the workarounds described below.

There is high demand and a discussion going on about Firebase Authentication emulator support. Unfortunately, it doesn’t exist yet. The situation is similar to Firestore: I want to be able to run my application locally without any external dependencies. As long as there is no emulator, there is no other way than to implement a simple mock.

There is nothing complicated in either implementation.

The frontend’s getJwtToken is implemented by generating a JWT token with mock secret.

The backend, instead of calling Firebase to verify the token, checks if the JWT was generated with mock secret.

This gives us some confidence that our flow is implemented more or less correctly. But is there any way to test it with production Firebase locally?

Firebase Authentication for local dev

Mock authentication does not give us 100% confidence that the flow is working correctly. We should be able to test Firebase Authentication locally. To do that, you need to take some extra steps.

It is not straightforward. If you are not changing anything in the authentication, you can probably skip this part.

First of all, you need to generate a service account file into the repository.

Note

Remember to not share it with anyone!

Don’t worry, it’s already in .gitignore.

gcloud auth login

gcloud iam service-accounts keys create service-account-file.json --project [YOUR PROJECT ID] --iam-account [YOUR PROJECT ID]@appspot.gserviceaccount.com

Next, you need to uncomment all lines linking service account in docker-compose.yml

volumes:

- ./pkg:/pkg

-# - ./service-account-file.json:$SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE

+ - ./service-account-file.json:$SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE

working_dir: /pkg/trainer

ports:

- "127.0.0.1:3000:$PORT"

context: ./dev/docker/app

volumes:

- ./pkg:/pkg

-# - ./service-account-file.json:$SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE

+ - ./service-account-file.json:$SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE

working_dir: /pkg/trainer

@ ... do it for all services!

After that, you should set GCP_PROJECT to your project id, uncomment SERIVCE_ACCOUNT_FILE and set MOCK_AUTH to false in .env

-GCP_PROJECT=threedotslabs-cloudnative

+GCP_PROJECT=YOUR-PROJECT-ID

PORT=3000

-FIRESTORE_PROJECT_ID=threedotslabs-cloudnative

+FIRESTORE_PROJECT_ID=YOUR-PROJECT-ID

FIRESTORE_EMULATOR_HOST=firestore:8787

# env used by karhoo/firestore-emulator container

-GCP_PROJECT_ID=threedotslabs-cloudnative

+GCP_PROJECT_ID=YOUR-PROJECT-ID

TRAINER_GRPC_ADDR=trainer-grpc:3000

USERS_GRPC_ADDR=users-grpc:3000

@ ...

CORS_ALLOWED_ORIGINS=http://localhost:8080

-#SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE=/service-account-file.json

-MOCK_AUTH=true

+SERVICE_ACCOUNT_FILE=/service-account-file.json

+MOCK_AUTH=false

LOCAL_ENV=true

-const MOCK_AUTH = process.env.NODE_ENV === 'development'

+const MOCK_AUTH = false

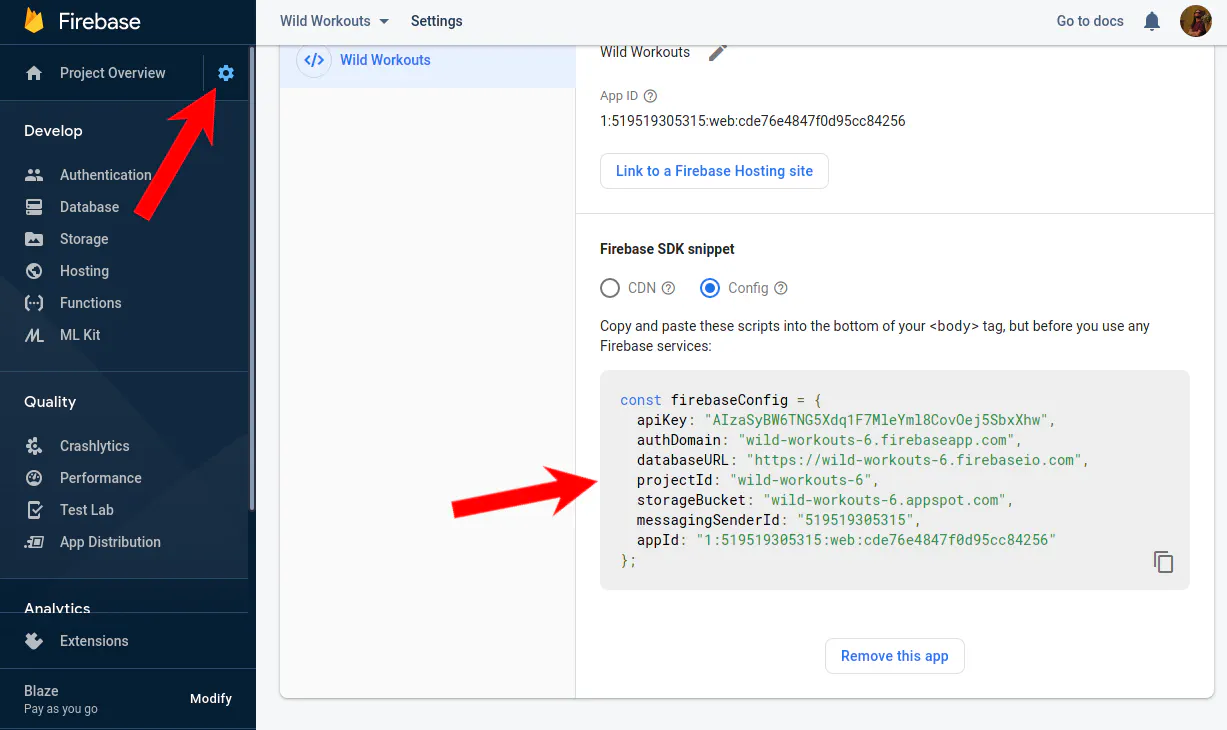

Now you need to go to Project Settings (you can find it after clicking the gear icon right to Project overview) and update your Firebase settings in web/public/__/firebase/init.json.

- "apiKey": "",

- "appId": "",

- "authDomain": "",

- "databaseURL": "",

- "messagingSenderId": "",

- "projectId": "",

- "storageBucket": ""

+ "apiKey": "AIzaSyBW6TNG5Xdq1F7MleYml8CovOej5SbxXhw",

+ "authDomain": "wild-workouts-6.firebaseapp.com",

+ "databaseURL": "https://wild-workouts-6.firebaseio.com",

+ "projectId": "wild-workouts-6",

+ "storageBucket": "wild-workouts-6.appspot.com",

+ "messagingSenderId": "519519305315",

+ "appId": "1:519519305315:web:cde76e4847f0d95cc84256"

}

The last thing is stopping and starting again docker-compose to reload envs and links.

And that’s all

As you can see, the setup was straightforward. We were able to save a lot of time. The situation could be more complicated if we didn’t want to host our application on Firebase. Our idea from the beginning was to prepare a simple base for future articles.

We didn’t exhaust the topic of authentication in this article. But for now, we don’t plan to explore authentication any deeper.

Maybe you have some good or bad experiences with any authentication solution in Go? Please share in the comments, so all readers can profit from that! 👍In this series, we would like to show you how to build applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. Maybe you’ve seen examples of Domain-Driven Design or Clean Architecture in Go. Most of them are not done in a pragmatic way that works within the language context.

In following articles, we will show patterns that we have successfully used in teams we’ve led for a couple of years. We will also show when applying them makes sense and when it’s over-engineering or CV-Driven Development. I’m sure that it will make you rethink your point of view on these techniques. 😉

That’s all for today. The next article will be available in 1-2 weeks. Please join our newsletter if you don’t want to miss it! 😉