Building a serverless application with Go, Google Cloud Run and Firebase

Welcome to the first article from the series covering how to build business-oriented applications in Go! In this series, we want to show you how to build applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term.

This series doesn’t focus too heavily on infrastructure and implementation details. But we need some foundation to build on later. In this article, we start by covering some basic tools from Google Cloud that can help us to do that.

Note

This is not just another article with random code snippets.

This post is part of a bigger series where we show how to build Go applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. We are doing it by sharing proven techniques based on many experiments we did with teams we lead and scientific research.

You can learn these patterns by building with us a fully functional example Go web application – Wild Workouts.

We did one thing differently – we included some subtle issues to the initial Wild Workouts implementation. Have we lost our minds to do that? Not yet. 😉 These issues are common for many Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and stop adding new features.

It’s one of the essential skills of a senior or lead developer; you always need to keep long-term implications in mind.

We will fix them by refactoring Wild Workouts. In that way, you will quickly understand the techniques we share.

Do you know that feeling after reading an article about some technique and trying implement it only to be blocked by some issues skipped in the guide? Cutting these details makes articles shorter and increases page views, but this is not our goal. Our goal is to create content that provides enough know-how to apply presented techniques. If you did not read previous articles from the series yet, we highly recommend doing that.

We believe that in some areas, there are no shortcuts. If you want to build complex applications in a fast and efficient way, you need to spend some time learning that. If it was simple, we wouldn’t have large amounts of scary legacy code.

Here’s the full list of 14 articles released so far.

The full source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. Don’t forget to leave a star for our project! ⭐

Note

State of this article in 2026

It’s interesting to see how things have changed since we wrote this article in 2020.

There were many changes on the frontend: Vue.js and Bootstrap are now obsolete in favor of React and Tailwind CSS.

But as a contrast, not much has changed on the backend side!

This matters for long-term maintainability: you don’t want to rewrite your backend every six years because a shiny new framework appeared.

With Go and solid architectural patterns, this stability is achievable.

The only big difference is that we no longer recommend Firebase/Firestore by default.

Our advice now: just use PostgreSQL.

It’s easier to operate and simpler to migrate between cloud providers if needed (or even host it on a VM).

We still recommend abstracting your database behind interfaces as described in The Repository Pattern article, which makes changing such decisions straightforward.

That’s about it. The backend content here hasn’t become outdated in six years, and it won’t in the next six or more. That’s the power of learning timeless patterns over chasing the newest tools. Your knowledge compounds over time instead of requiring you to constantly relearn everything.

Why serverless?

Running a Kubernetes cluster requires a lot of support from “DevOps teams”. Let’s skip the fact that DevOps is not a job title for now.

Slide from The gordian knot - Alberto Brandolini

Small applications that could easily run on one virtual machine now get deployed on highly complex Kubernetes clusters. All these clusters require significant maintenance.

On the other hand, moving applications to containers has given us significant flexibility in building and deploying them. It enabled rapid deployments of hundreds of microservices with considerable autonomy. But the cost is high.

Wouldn’t it be great if a fully managed solution existed? 🤔

Maybe your company already uses a managed Kubernetes cluster. If so, you probably know that even a managed cluster still requires substantial “DevOps” support.

Maybe serverless? Well, splitting a big application into multiple, independent Lambdas (Cloud Functions) is a great way to create an unmaintainable cataclysm.

But wait, is it the only way to build serverless applications? No!

Google Cloud Run

The idea behind Google Cloud Run is simple: you just need to provide a Docker container, and Google Cloud runs it.

Inside this container, you can run an application written in any language that can expose a port with your HTTP or gRPC API.

You’re not limited to synchronous processing: you can also process Pub/Sub messages inside this container.

And that’s all that you need from the infrastructure side. Google Cloud does all the magic. Based on the traffic, the container will automatically scale up and down. Sounds like a perfect solution?

In practice, it is not so simple. Many articles show how to use Google Cloud Run, but they usually present small building blocks you can use to build an application. It’s hard to combine all these pieces from multiple places into a fully working project (been there, done that).

Most of these articles ignore the problem of vendor lock-in. The deployment method should be just an implementation detail. I covered this topic in the Why using Microservices or Monolith can be just a detail? article in 2018.

But most importantly, using the newest and shiniest technologies doesn’t mean your application won’t become hated legacy in the next 3 months.

Serverless solves only infrastructure challenges. It doesn’t stop you from building an application that is hard to maintain. I even have the impression that it’s the opposite: these fancy applications sooner or later become the hardest to maintain.

For this series of articles, we created a fully functional, real-life application. You can deploy this application to Google Cloud with one command using Terraform. You can run a local copy with a single docker-compose command.

There is also one thing we’re doing differently than others. We included some subtle issues that, from our observations, are common in Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and prevent us from adding new features.

Have we lost our minds? Not yet. 😉 This approach will help you understand which issues you can solve and which techniques help. It’s also a test for the practices we use. If something isn’t a problem, why use any technique to solve it?

Plan

In the next few articles, we cover all topics related to running the application on Google Cloud. In this part, we didn’t add any issues or bad practices. 😉 The first articles may be a bit basic if you already have some experience in Go. We want to ensure that if you’re just starting with Go, you’ll be able to follow the more complex topics that come next.

Next, we refactor parts of the application that handle business logic. This part will be much more complex.

Running the project locally

The ability to run a project locally is critical for efficient development. It’s frustrating when you can’t check your changes quickly and easily.

It’s much harder to achieve it for projects built from hundreds of microservices. Fortunately, our project has only 5 services. 😉

In Wild Workouts, we created a Docker Compose setup with live code reloading for both frontend and backend.

For the frontend, we use a container with the vue-cli-service serve tool.

For the backend, the situation is a bit more complex.

In all containers, we run the reflex tool. reflex listens for code changes and triggers recompilation of the service.

If you’re interested in the details, you can find them in our Go Docker dev environment with Go Modules and live code reloading blog post.

Requirements

The only requirements needed to run the project are Docker and Docker Compose.

Running

git clone https://github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example.git && cd wild-workouts-go-ddd-example

And run Docker Compose:

docker-compose up

After downloading all JavaScript and Go dependencies, you should see a message with the frontend address:

web_1 | $ vue-cli-service serve

web_1 | INFO Starting development server...

web_1 | DONE Compiled successfully in 6315ms11:18:26 AM

web_1 |

web_1 |

web_1 | App running at:

web_1 | - Local: http://localhost:8080/

web_1 |

web_1 | It seems you are running Vue CLI inside a container.

web_1 | Access the dev server via http://localhost:<your container's external mapped port>/

web_1 |

web_1 | Note that the development build is not optimized.

web_1 | To create a production build, run yarn build.

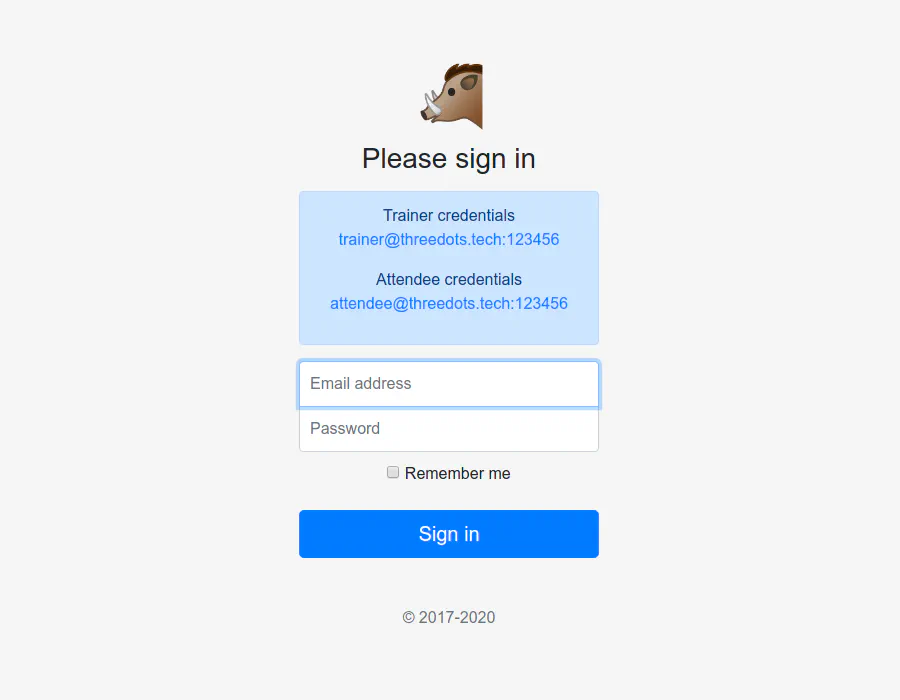

Congratulations! Your local version of the Wild Workouts application is available at http://localhost:8080/.

There is also a public version available at https://threedotslabs-wildworkouts.web.app.

What Wild Workouts can do?

How often have you seen tutorials without any real-life functionality? How often have patterns from these tutorials failed in real projects? Probably too often. 😉 Real life is not as simple as tutorials suggest.

To avoid this problem, we created Wild Workouts as a fully functional project. It’s much harder to take shortcuts and skip complexity when an application needs to be complete. This makes all articles longer, but there are no shortcuts here. If you don’t spend enough time at the beginning, you’ll lose much more time later during implementation. Or worse: you’ll be fixing problems in a rush with the application already running in production.

tl;dr

Wild Workouts is an application for personal gym trainers and attendees.

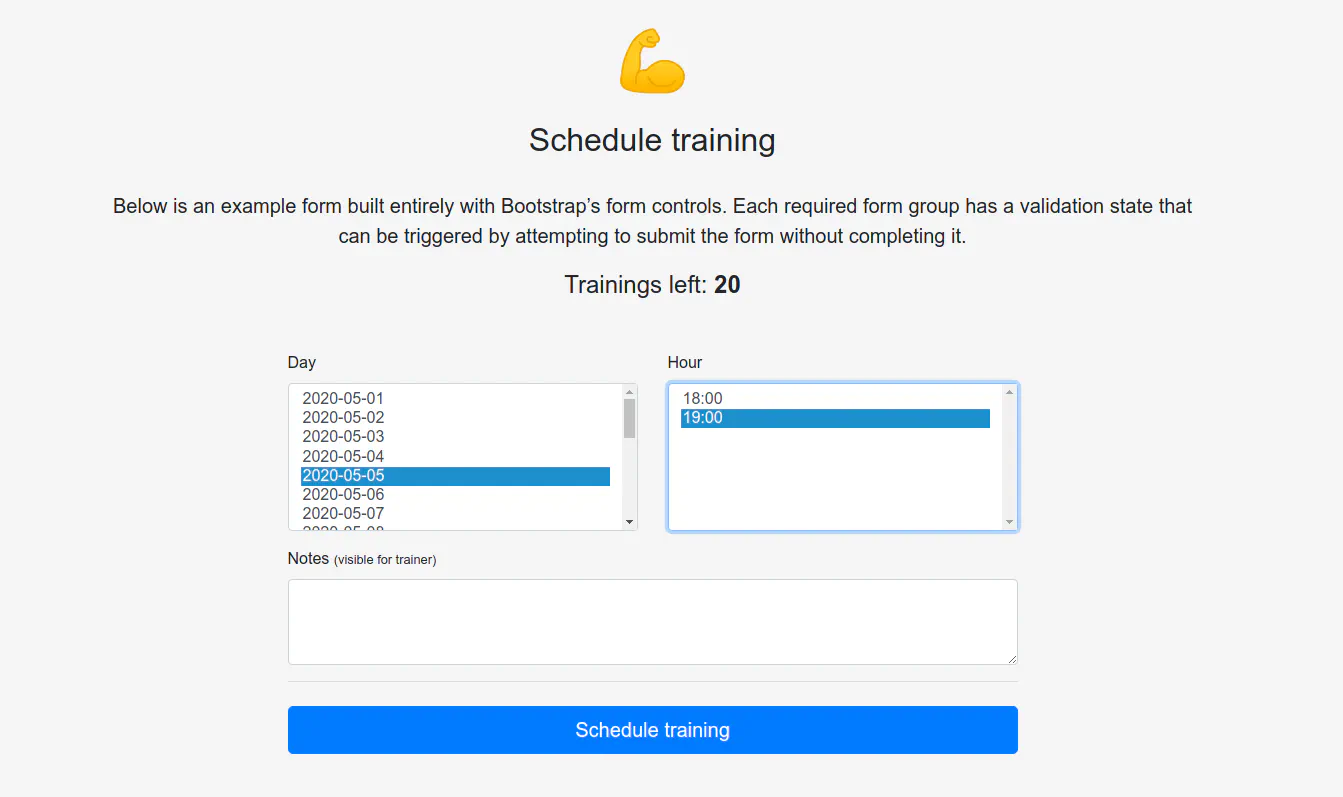

Trainers can set a schedule for when they are available for training.

Attendees can schedule training for available dates.

Other functionalities are:

- management of “credits” (how many trainings the attendee can schedule)

- cancellation

- if a training is canceled less than 24 hours before it begins, the attendee will not receive their credits back

- training reschedule

- if someone wants to reschedule a training less than 24 hours before it begins, the other participant (trainer or attendee) must approve it

- calendar view

Sounds simple. What can go wrong? 🤔

Frontend

If you are not interested in the frontend part, you can go straight to the Backend section.

I’m primarily a backend engineer, and to be honest, I’m not the greatest JavaScript or frontend specialist. 😉 But we can’t have an end-to-end application without a frontend!

In this series, we focus on the backend part. I’ll give a high-level overview of the technologies I used on the frontend. This will be nothing new if you have any basic frontend knowledge. For more details, I recommend checking the source code in the web/ directory.

If you want to know more about how the frontend is built, please let us know in the comments!OpenAPI (Swagger) client

Nobody likes keeping API contracts up to date manually. It’s tedious and counterproductive to keep multiple JSON files in sync. OpenAPI solves this problem by generating a JavaScript HTTP client and Go HTTP server from the provided specification. We dive into the details in the Backend part.

Bootstrap

You probably already know Bootstrap, the greatest friend of every backend engineer, like me. 😉 Wrestling with HTML and CSS is the part of frontend development I dislike the most. Bootstrap provided almost all the building blocks I needed for the application’s HTML.

Vue.js

After evaluating several popular frontend frameworks, I decided to use Vue.js. I really enjoyed its simplicity.

I started my journey as a full-stack developer in the pre-jQuery era. Frontend tooling has made huge progress… but I’ll stay with the backend for now. 😉

Backend

The backend of Wild Workouts is built from 3 services.

trainer– provides public HTTP and internal gRPC endpoints for managing trainer scheduletrainings– provides public HTTP for managing attendee trainingsusers– provides public HTTP endpoints and internal gRPC endpoints , manages credits and user data

If a service exposes 2 types of APIs, each of them is exposed in a separate process.

Public HTTP API

Most operations performed by applications are triggered by the public HTTP API.

I’ve heard Go newcomers ask many times what framework they should use to create an HTTP service.

I always advise against using any kind of HTTP framework in Go.

A simple router, like chi, is more than enough.

chi provides only the lightweight glue to define what URLs and methods our API supports.

Under the hood, it uses the Go standard library http package, so all related tools like middlewares are 100% compatible.

It may feel strange not to use a framework if you’re coming from a language where Spring, Symfony, Django, or Express are the obvious choices. It felt strange to me too. Using any framework in Go adds unnecessary complexity and couples your project with that framework. KISS. 😉

All the services run the HTTP server in the same way. It makes sense not to copy this code three times.

func RunHTTPServer(createHandler func(router chi.Router) http.Handler) {

apiRouter := chi.NewRouter()

setMiddlewares(apiRouter)

rootRouter := chi.NewRouter()

// we are mounting all APIs under /api path

rootRouter.Mount("/api", createHandler(apiRouter))

logrus.Info("Starting HTTP server")

http.ListenAndServe(":"+os.Getenv("PORT"), rootRouter)

}

chi provides a set of useful built-in HTTP middlewares, but we’re not limited to them. All middlewares compatible with the Go standard library will work.

Note

Long story short: middlewares allow us to do anything before and after a request is executed (with access to the http.Request).

Using HTTP middlewares gives us significant flexibility in building our custom HTTP server.

We build our server from multiple decoupled components that you can customize for your needs.

func setMiddlewares(router *chi.Mux) {

router.Use(middleware.RequestID)

router.Use(middleware.RealIP)

router.Use(logs.NewStructuredLogger(logrus.StandardLogger()))

router.Use(middleware.Recoverer)

addCorsMiddleware(router)

addAuthMiddleware(router)

router.Use(

middleware.SetHeader("X-Content-Type-Options", "nosniff"),

middleware.SetHeader("X-Frame-Options", "deny"),

)

router.Use(middleware.NoCache)

}

We have our framework almost ready now. :) It’s time to use it. We can call server.RunHTTPServer in the trainings service.

package main

// ...

func main() {

// ...

server.RunHTTPServer(func(router chi.Router) http.Handler {

return HandlerFromMux(HttpServer{firebaseDB, trainerClient, usersClient}, router)

})

}

createHandler needs to return http.Handler.

In our case, it is HandlerFromMux generated by oapi-codegen.

It provides us all the paths and query parameters from the OpenAPI specs.

// HandlerFromMux creates http.Handler with routing matching OpenAPI spec based on the provided mux.

func HandlerFromMux(si ServerInterface, r chi.Router) http.Handler {

r.Group(func(r chi.Router) {

r.Use(GetTrainingsCtx)

r.Get("/trainings", si.GetTrainings)

})

r.Group(func(r chi.Router) {

r.Use(CreateTrainingCtx)

r.Post("/trainings", si.CreateTraining)

})

// ...

# ...

paths:

/trainings:

get:

operationId: getTrainings

responses:

'200':

description: todo

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Trainings'

default:

description: unexpected error

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Error'

# ...

If you make changes to the OpenAPI spec, you need to regenerate the Go server and JavaScript clients. Run:

make openapi

Part of the generated code is ServerInterface.

It contains all methods the API must support.

You implement server functionality by implementing this interface.

type ServerInterface interface {

// (GET /trainings)

GetTrainings(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request)

// (POST /trainings)

CreateTraining(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request)

// ...

}

This is an example of how trainings.HttpServer is implemented:

package main

import (

"net/http"

"github.com/go-chi/render"

"github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/pkg/internal/auth"

"github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/pkg/internal/genproto/trainer"

"github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/pkg/internal/genproto/users"

"github.com/ThreeDotsLabs/wild-workouts-go-ddd-example/pkg/internal/server/httperr"

)

type HttpServer struct {

db db

trainerClient trainer.TrainerServiceClient

usersClient users.UsersServiceClient

}

func (h HttpServer) GetTrainings(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user, err := auth.UserFromCtx(r.Context())

if err != nil {

httperr.Unauthorised("no-user-found", err, w, r)

return

}

trainings, err := h.db.GetTrainings(r.Context(), user)

if err != nil {

httperr.InternalError("cannot-get-trainings", err, w, r)

return

}

trainingsResp := Trainings{trainings}

render.Respond(w, r, trainingsResp)

}

// ...

But HTTP paths are not the only thing generated from the OpenAPI spec. More importantly, it also provides the models for responses and requests. Models are, in most cases, much more complex than API paths and methods. Generating them saves time and frustration during API contract changes.

# ...

schemas:

Training:

type: object

required: [uuid, user, userUuid, notes, time, canBeCancelled, moveRequiresAccept]

properties:

uuid:

type: string

format: uuid

user:

type: string

example: Mariusz Pudzianowski

userUuid:

type: string

format: uuid

notes:

type: string

example: "let's do leg day!"

time:

type: string

format: date-time

canBeCancelled:

type: boolean

moveRequiresAccept:

type: boolean

proposedTime:

type: string

format: date-time

moveProposedBy:

type: string

Trainings:

type: object

required: [trainings]

properties:

trainings:

type: array

items:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Training'

# ...

// Training defines model for Training.

type Training struct {

CanBeCancelled bool `json:"canBeCancelled"`

MoveProposedBy *string `json:"moveProposedBy,omitempty"`

MoveRequiresAccept bool `json:"moveRequiresAccept"`

Notes string `json:"notes"`

ProposedTime *time.Time `json:"proposedTime,omitempty"`

Time time.Time `json:"time"`

User string `json:"user"`

UserUuid string `json:"userUuid"`

Uuid string `json:"uuid"`

}

// Trainings defines model for Trainings.

type Trainings struct {

Trainings []Training `json:"trainings"`

}

Cloud Firestore database

All right, we have the HTTP API. But even the best API is useless without data and the ability to persist it.

If we want to build the application in the most modern, scalable, and truly serverless way, Firestore is a natural choice. We get all of that out of the box. What’s the cost?

For the Europe multi-region option, you pay:

- $0.06 per 100,000 documents reads

- $0.18 per 100,000 documents writes

- $0.02 per 100,000 documents deletes

- $0.18/GiB of stored data/month

Sounds pretty cheap?

For comparison, let’s take the cheapest Cloud SQL MySQL db-f1-micro instance with a shared Virtual CPU and 3 GB of storage as a reference: it costs $15.33/month.

The cheapest instance with high availability and with 1 non-shared Virtual CPU costs $128.21/month.

Even better, in the free plan, you can store up to 1 GiB of data with 20k document writes per day.

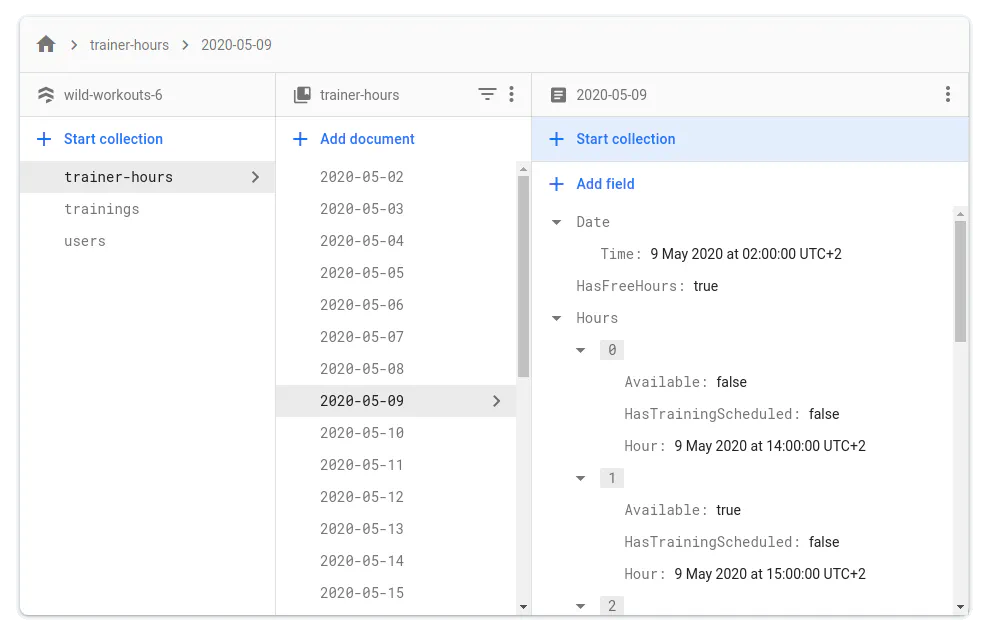

Firestore is a NoSQL database, so we shouldn’t expect to build relational models the SQL way. Instead, we have a system of hierarchical collections. In our case, the data model is simple, so we have only one level of collections.

Unlike many NoSQL databases, Firestore offers ACID transactions on any operation. This also works when updating multiple documents.

Firestore limitations

An important limitation is 1 update per second per document. You can still update many independent documents in parallel. This is an important factor to consider when designing your database. In some cases, you should consider batching operations, different document designs, or using a different database. If data changes frequently, a key-value database might be a good choice.

In my experience, the 1 update per second per document limitation isn’t a serious problem. In most cases when I used Firestore, we were updating many independent documents. This also applies when using Firestore for event sourcing: you only use append operations. In Wild Workouts, we shouldn’t have a problem with this limit. 😉

Note

I have also observed that Firestore needs some time to warm up. In other words, if you want to insert 10 million documents within one minute after setting up a new project, it may not work. I assume this is related to some internal mechanism that handles scalability.

Fortunately, in the real world, traffic spikes from 0 to 10 million writes per minute are uncommon.

Running Firestore locally

Unfortunately, the Firestore emulator is not perfect. 😉 I found some situations where the emulator wasn’t 100% compatible with the real version. I also encountered situations where updating and reading the same document in a transaction caused a deadlock. From my perspective, this functionality is sufficient for local development.

The alternative is to have a separate Google Cloud project for local development. I prefer having a local environment that is truly local and doesn’t depend on any external services. It’s also easier to set up and can be used later in continuous integration.

Since the end of May, the Firestore emulator provides a UI. It is added to the Docker Compose and is available at http://localhost:4000/. At the time of writing, sub-collections aren’t displayed properly in the emulator UI. Don’t worry, for Wild Workouts this isn’t a problem. 😉

Using Firestore

Apart from the Firestore implementation, the code works the same way locally and in production.

When using the emulator locally, we need to run our application with the FIRESTORE_EMULATOR_HOST environment variable set to the emulator hostname (in our case firestore:8787).

This is set in the .env file.

In production, Google Cloud handles everything under the hood, and no extra configuration is needed.

firebaseClient, err := firestore.NewClient(ctx, os.Getenv("GCP_PROJECT"))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

Here’s an example of how I used the Firestore client to query the trainer schedule. You can see how I used the queries functionality to get only dates within the queried date interval.

package main

import (

// ...

"cloud.google.com/go/firestore"

// ...

)

// ...

type db struct {

firestoreClient *firestore.Client

}

func (d db) TrainerHoursCollection() *firestore.CollectionRef {

return d.firestoreClient.Collection("trainer-hours")

}

// ...

func (d db) QueryDates(params *GetTrainerAvailableHoursParams, ctx context.Context) ([]Date, error) {

iter := d.

TrainerHoursCollection().

Where("Date.Time", ">=", params.DateFrom).

Where("Date.Time", "<=", params.DateTo).

Documents(ctx)

var dates []Date

for {

doc, err := iter.Next()

if err == iterator.Done {

break

}

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

date := Date{}

if err := doc.DataTo(&date); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

date = setDefaultAvailability(date)

dates = append(dates, date)

}

return dates, nil

}

No extra data mapping is needed. The Firestore library can marshal any struct with public fields or map[string]interface, as long as there’s nothing unusual inside. 😉

You can find the full specification of how conversion works in the cloud.google.com/go/firestore GoDoc.

type Date struct {

Date openapi_types.Date `json:"date"`

HasFreeHours bool `json:"hasFreeHours"`

Hours []Hour `json:"hours"`

}

date := Date{}

if err := doc.DataTo(&date); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

Production deployment tl;dr

You can deploy your own version of Wild Workouts with one command:

> cd terraform/

> make

Fill all required parameters:

project [current: wild-workouts project]: # <----- put your Wild Workouts Google Cloud project name here (it will be created)

user [current: email@gmail.com]: # <----- put your Google (Gmail, G-suite etc.) e-mail here

billing_account [current: My billing account]: # <----- your billing account name, can be found here https://console.cloud.google.com/billing

region [current: europe-west1]:

firebase_location [current: europe-west]:

# it may take a couple of minutes...

The setup is almost done!

Now you need to enable Email/Password provider in the Firebase console.

To do this, visit https://console.firebase.google.com/u/0/project/[your-project]/authentication/providers

You can also downgrade the subscription plan to Spark (it's set to Blaze by default).

The Spark plan is completely free and has all features needed for running this project.

Congratulations! Your project should be available at: https://[your-project].web.app

If it's not, check if the build finished successfully: https://console.cloud.google.com/cloud-build/builds?project=[your-project]

If you need help, feel free to contact us at https://threedots.tech

We describe the deployment in detail in the next articles.

What’s next?

That’s all for today. In the next article, I will cover internal gRPC communication between services. After that, I will cover HTTP Firebase authentication.The code with gRPC communication and authentication is already on our GitHub. Feel free to read, run, and experiment with it.

Deployment and infrastructure

In parallel, Miłosz is working on articles describing the deployment and infrastructure part. They will cover in detail:

- Terraform

- Cloud Run

- CI/CD

- Firebase hosting

What is wrong with this application?!

After finishing all articles describing the current application, we start the part related to refactoring and adding new features to Wild Workouts.

We don’t want to use many fancy techniques just to make our CVs look better. Our goal is to solve issues present in the application using Domain-Driven Design, Clean Architecture, CQRS, Event Storming, and Event Modeling.

We do this through refactoring. It should then be clear what issues are solved and how the implementation becomes cleaner. Maybe during this process we’ll even discover that some of these techniques aren’t useful in Go. Who knows? 😉

Do you see any of the issues we included in this application? Please post your guess in the comments. :)

See you next week.