Introduction to DDD Lite: When microservices in Go are not enough

When I started working in Go, the community did not look favorably on techniques like DDD (Domain-Driven Design) and Clean Architecture. I heard multiple times: “Don’t do Java in Golang!”, “I’ve seen that in Java, please don’t!”.

At the time, I already had almost 10 years of experience in PHP and Python. I’d seen too many bad things there. I remember all those “Eight-thousanders” (methods with 8k+ lines of code 😉) and applications that nobody wanted to maintain. When I checked the git history of these ugly monsters, they all looked harmless in the beginning. But over time, small, innocent problems grew more significant and more serious. I’d also seen how DDD and Clean Architecture solved these issues.

Maybe Golang is different? Maybe writing microservices in Golang will fix this issue?

It was supposed to be so beautiful

Now, after exchanging experience with many people and seeing a lot of codebases, my point of view is clearer than 3 years ago. Unfortunately, I’m far from thinking that just using Go and microservices will save us from all the issues I encountered earlier. I started having flashbacks from the old, bad times.

It’s less visible because of relatively younger codebases. It’s less visible because of Go’s design. But I’m sure that over time, we’ll have more and more legacy Go applications that nobody wants to maintain.

Fortunately, 3 years ago, despite the chilly reception, I didn’t give up. I decided to try using DDD and related techniques that had worked for me previously in Go. With Miłosz, we led teams for 3 years that were all successfully using DDD, Clean Architecture, and other not-popular-enough techniques in Go. They gave us the ability to develop our applications and products at constant velocity, regardless of the code’s age.

It was obvious from the beginning that moving patterns 1:1 from other technologies would not work. Crucially, we did not abandon idiomatic Go code and microservices architecture: they fit together perfectly!

Today I’d like to share with you the first, most straightforward technique: DDD Lite.

State of DDD in Golang

Before sitting down to write this article, I checked a couple of articles about DDD in Go on Google. I’ll be brutal here: they all miss the most critical points that make DDD work. If I imagined reading these articles without any DDD knowledge, I would not be encouraged to use them in my team. This superficial approach may also be why DDD is still not widely adopted in the Go community.

In this series, we try to show all essential techniques in the most pragmatic way. Before describing any patterns, we start with a question: what does this give us? It’s an excellent way to challenge our current thinking.

I’m sure we can change how the Go community receives these techniques. We believe they are the best way to implement complex business projects. I believe we will help establish Go as a great language for building not only infrastructure but also business software.

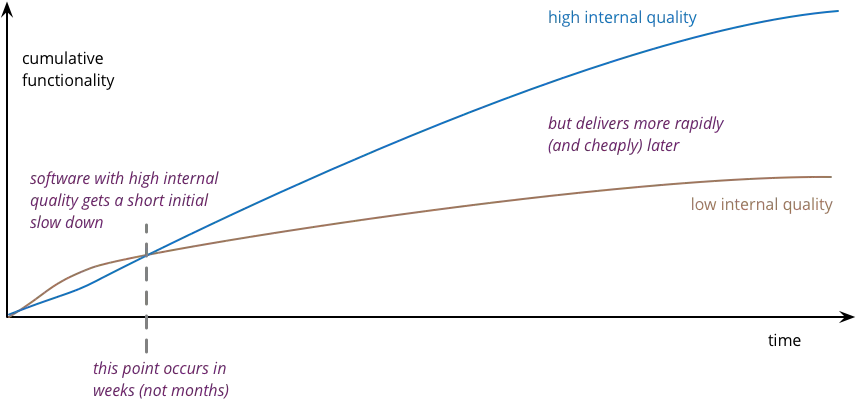

You need to go slow, to go fast

It may be tempting to implement your project in the simplest way. It’s even more tempting when you feel pressure from “the top”. We’re using microservices, though, right? If needed, we’ll just rewrite the service? I’ve heard that story many times, and it rarely had a happy ending. 😉 It’s true that taking shortcuts saves time. But only in the short term.

Consider the example of tests of any kind. You can skip writing tests at the beginning of the project. You’ll obviously save some time, and management will be happy. The calculation seems simple: the project was delivered faster.

But this shortcut is not worthwhile in the long term. As the project grows, your team will become afraid of making any changes. In the end, you’ll spend more total time than if you had implemented tests from the beginning. You will slow down in the long term because you sacrificed quality for a quick performance boost at the start. On the other hand, if a project is not critical and needs to ship fast, you can skip tests. It should be a pragmatic decision, not just “we know better, and we don’t create bugs”.

The case is the same for DDD. When you use DDD, you need a bit more time in the beginning, but the long-term savings are enormous. However, not every project is complex enough to warrant advanced techniques like DDD.

There is no quality vs. speed tradeoff in the long run. If you want to go fast in the long term, you need to maintain high quality.

That’s great, but do you have any evidence it works?

If you asked me this question two years ago, I would have said: “Well, I feel that it works better!”. But just trusting my words may not be enough. 😉 Many tutorials show dumb ideas and claim they work without any evidence. Let’s not trust them blindly!

Just a reminder: if someone has a couple thousand Twitter followers, that alone is not a reason to trust them!

Fortunately, 2 years ago Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations was released. In brief, this book describes what factors affect development teams’ performance. But the reason this book became famous is that it’s not just a set of unvalidated ideas: it’s based on scientific research.

I was most interested in the part showing what allows teams to be top performers. This book shows some obvious facts, like introducing DevOps, CI/CD, and loosely coupled architecture, which are all essential factors in high-performing teams.

Note

If things like DevOps and CI/CD are not obvious to you, you can start with these books: The Phoenix Project and The DevOps Handbook.

What does Accelerate tell us about top-performing teams?

We found that high performance is possible with all kinds of systems, provided that systems and the teams that build and maintain them—are loosely coupled.

This key architectural property enables teams to easily test and deploy individual components or services even as the organization and the number of systems it operates grow—that is, it allows organizations to increase their productivity as they scale.

So let’s use microservices, and we are done? I would not be writing this article if it was enough. 😉

- Make large-scale changes to the design of their system without depending on other teams to make changes in their systems or creating significant work for other teams

- Complete their work without communicating and coordinating with people outside their team

- Deploy and release their product or service on demand, regardless of other services it depends upon

- Do most of their testing on demand, without requiring an integrated test environment Perform deployments during normal business hours with negligible downtime

Unfortunately, in real life, many so-called service-oriented architectures don’t permit testing and deploying services independently of each other, and thus will not enable teams to achieve higher performance.

[…] employing the latest whizzy microservices architecture deployed on containers is no guarantee of higher performance if you ignore these characteristics. […] To achieve these characteristics, design systems are loosely coupled — that is, can be changed and validated independently of each other.

Using microservices architecture and splitting services into small pieces is not enough. If done the wrong way, it adds extra complexity and slows teams down. DDD can help us here.

I’m mentioning DDD multiple times. What is DDD, actually?

What is DDD (Domain-Driven Design)

Let’s start with the Wikipedia definition:

Domain-driven design (DDD) is the concept that the structure and language of your code (class names, class methods, class variables) should match the business domain. For example, if your software processes loan applications, it might have classes such as LoanApplication and Customer, and methods such as AcceptOffer and Withdraw.

Well, it’s not the perfect definition. 😅 It’s still missing some of the most important points.

It’s also worth mentioning that DDD was introduced in 2003. That’s a pretty long time ago. Some distillation may help put DDD in the 2020 and Go context.

Note

If you are interested in some historical context on when DDD was created, you should check Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software by the DDD creator - Eric Evans

Please print this and hang over the bed to receive +10 DDD blessing.

My simple DDD definition is: Ensure that you solve a valid problem in the optimal way. Then implement the solution so that your business stakeholders understand it without any translation from technical language.

How to achieve that?

Coding is a war, to win you need a strategy!

I like to say that “5 days of coding can save 15 minutes of planning”.

Before starting to write any code, you should ensure that you’re solving a valid problem. This may sound obvious, but from my experience, it’s not as easy as it sounds. It’s often the case that the solution engineers create doesn’t actually solve the problem the business requested. A set of patterns that helps us in this area is called Strategic DDD patterns.

From my experience, DDD Strategic Patterns are often skipped. The reason is simple: we’re all developers, and we like to write code rather than talk to the “business people”. 😉 Unfortunately, this approach of staying closed in a basement without talking to any business people has many downsides. Lack of trust from the business, lack of knowledge of how the system works (from both business and engineering sides), solving the wrong problems: these are just some of the most common issues.

The good news is that in most cases, this is caused by a lack of proper techniques like Event Storming. They can benefit both sides. What’s also surprising is that talking to the business may be one of the most enjoyable parts of the work!

That said, we’ll start with patterns that apply to the code. They can give us some advantages of DDD. They’ll also be useful for you sooner. Without Strategic patterns, I’d say you’ll only get 30% of the advantages that DDD can offer. We’ll return to Strategic patterns in the next articles.

DDD Lite in Go

After a pretty long introduction, it’s finally time to touch some code! In this article, we’ll cover some basics of Tactical Domain-Driven Design patterns in Go. Keep in mind that this is just the beginning. We’ll need a few more articles to cover the entire topic.

One of the most crucial parts of Tactical DDD is reflecting the domain logic directly in the code.

But that’s still a vague definition, and it’s not needed at this point. I also don’t want to start by describing what Value Objects, Entities, and Aggregates are. Let’s start with practical examples instead.

Wild workouts

I haven’t mentioned yet that we created an entire application called Wild Workouts especially for these articles. Interestingly, we introduced some subtle issues in this application to have something to refactor. If Wild Workouts looks like an application you’re working on, you’d better stay with us for a moment. 😉

Note

This is not just another article with random code snippets.

This post is part of a bigger series where we show how to build Go applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. We are doing it by sharing proven techniques based on many experiments we did with teams we lead and scientific research.

You can learn these patterns by building with us a fully functional example Go web application – Wild Workouts.

We did one thing differently – we included some subtle issues to the initial Wild Workouts implementation. Have we lost our minds to do that? Not yet. 😉 These issues are common for many Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and stop adding new features.

It’s one of the essential skills of a senior or lead developer; you always need to keep long-term implications in mind.

We will fix them by refactoring Wild Workouts. In that way, you will quickly understand the techniques we share.

Do you know that feeling after reading an article about some technique and trying implement it only to be blocked by some issues skipped in the guide? Cutting these details makes articles shorter and increases page views, but this is not our goal. Our goal is to create content that provides enough know-how to apply presented techniques. If you did not read previous articles from the series yet, we highly recommend doing that.

We believe that in some areas, there are no shortcuts. If you want to build complex applications in a fast and efficient way, you need to spend some time learning that. If it was simple, we wouldn’t have large amounts of scary legacy code.

Here’s the full list of 14 articles released so far.

The full source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. Don’t forget to leave a star for our project! ⭐

Refactoring of trainer service

The first (micro)service that we’ll refactor is trainer.

We’ll leave other services untouched for now and return to them later.

This service is responsible for keeping the trainer schedule and ensuring that we can have only one training scheduled in one hour. It also keeps the information about available hours (trainer’s schedule).

The initial implementation was not the best. Even though there’s not a lot of logic, some parts of the code started to get messy. I also have a gut feeling, based on experience, that over time it will get worse. 😉

func (g GrpcServer) UpdateHour(ctx context.Context, req *trainer.UpdateHourRequest) (*trainer.EmptyResponse, error) {

trainingTime, err := grpcTimestampToTime(req.Time)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Error(codes.InvalidArgument, "unable to parse time")

}

date, err := g.db.DateModel(ctx, trainingTime)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Error(codes.Internal, fmt.Sprintf("unable to get data model: %s", err))

}

hour, found := date.FindHourInDate(trainingTime)

if !found {

return nil, status.Error(codes.NotFound, fmt.Sprintf("%s hour not found in schedule", trainingTime))

}

if req.HasTrainingScheduled && !hour.Available {

return nil, status.Error(codes.FailedPrecondition, "hour is not available for training")

}

if req.Available && req.HasTrainingScheduled {

return nil, status.Error(codes.FailedPrecondition, "cannot set hour as available when it have training scheduled")

}

if !req.Available && !req.HasTrainingScheduled {

return nil, status.Error(codes.FailedPrecondition, "cannot set hour as unavailable when it have no training scheduled")

}

hour.Available = req.Available

if hour.HasTrainingScheduled && hour.HasTrainingScheduled == req.HasTrainingScheduled {

return nil, status.Error(codes.FailedPrecondition, fmt.Sprintf("hour HasTrainingScheduled is already %t", hour.HasTrainingScheduled))

}

hour.HasTrainingScheduled = req.HasTrainingScheduled

Even though it’s not the worst code ever, it reminds me of what I saw when I checked the git history of the code I worked on. I can imagine that after some time, new features will arrive and it will become much worse.

It’s also hard to mock dependencies here, so there are also no unit tests.

The First Rule - reflect your business logic literally

While implementing your domain, you should stop thinking about structs as dummy data structures or “ORM-like” entities with a list of setters and getters. Instead, think about them as types with behavior.

When you talk with your business stakeholders, they say “I’m scheduling training at 13:00”, rather than “I’m setting the attribute state to ’training scheduled’ for hour 13:00.”.

They also don’t say: “you can’t set attribute status to ’training_scheduled’”. It is rather: “You can’t schedule training if the hour is not available”. How to put it directly in the code?

func (h *Hour) ScheduleTraining() error {

if !h.IsAvailable() {

return ErrHourNotAvailable

}

h.availability = TrainingScheduled

return nil

}

One question that can help us with implementation is: “Will business stakeholders understand my code without any translation of technical terms?”. You can see in that snippet that even a non-technical person will be able to understand when you can schedule training.

This approach’s cost is low, and it helps tackle complexity by making rules much easier to understand.

Even though the change is not big, we got rid of this wall of ifs that would become much more complicated in the future.

We’re also now able to easily add unit tests. What’s good: we don’t need to mock anything here.

The tests also serve as documentation that helps us understand how Hour behaves.

func TestHour_ScheduleTraining(t *testing.T) {

h, err := hour.NewAvailableHour(validTrainingHour())

require.NoError(t, err)

require.NoError(t, h.ScheduleTraining())

assert.True(t, h.HasTrainingScheduled())

assert.False(t, h.IsAvailable())

}

func TestHour_ScheduleTraining_with_not_available(t *testing.T) {

h := newNotAvailableHour(t)

assert.Equal(t, hour.ErrHourNotAvailable, h.ScheduleTraining())

}

Now, if anybody asks the question “When can I schedule training?”, you can quickly answer. In larger systems, the answer to this kind of question is even less obvious. Multiple times I spent hours trying to find all places where some objects were used in unexpected ways. The next rule will help us with that even more.

Testing Helpers

Note

Testing helpers were introduced in the next article. They are not available in this article’s diff. 😉

It’s useful to have helpers in tests for creating our domain entities.

For example: newExampleTrainingWithTime, newCanceledTraining, etc.

This also makes our domain tests much more readable.

Custom asserts, like assertTrainingsEquals, can also save a lot of duplication.

The github.com/google/go-cmp library is extremely useful for comparing complex structs.

It allows us to compare our domain types with private fields, skip some field validation, or implement custom validation functions.

func assertTrainingsEquals(t *testing.T, tr1, tr2 *training.Training) {

cmpOpts := []cmp.Option{

cmpRoundTimeOpt,

cmp.AllowUnexported(

training.UserType{},

time.Time{},

training.Training{},

),

}

assert.True(

t,

cmp.Equal(tr1, tr2, cmpOpts...),

cmp.Diff(tr1, tr2, cmpOpts...),

)

}

It’s also a good idea to provide a Must version of frequently used constructors, for example MustNewUser.

Unlike normal constructors, these panic if parameters are not valid (for tests, that’s not a problem).

func NewUser(userUUID string, userType UserType) (User, error) {

if userUUID == "" {

return User{}, errors.New("missing user UUID")

}

if userType.IsZero() {

return User{}, errors.New("missing user type")

}

return User{userUUID: userUUID, userType: userType}, nil

}

func MustNewUser(userUUID string, userType UserType) User {

u, err := NewUser(userUUID, userType)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

return u

}

The Second Rule: always keep a valid state in the memory

I recognize that my code will be used in ways I cannot anticipate, in ways it was not designed, and for longer than it was ever intended.

The world would be better if everyone took this quote into account. I’m not without fault here either. 😉

From my observation, when you’re sure that the object you use is always valid, it helps avoid a lot of ifs and bugs.

You’ll also feel much more confident knowing that you can’t do anything stupid with the current code.

I have many flashbacks of being afraid to make changes because I wasn’t sure of the side effects. Developing new features is much slower without confidence that you’re using the code correctly!

Our goal is to do validation in only one place (good DRY) and ensure that nobody can change the internal state of Hour.

The only public API of the object should be methods describing behaviors. No dumb getters and setters!

We also need to put our types in a separate package and make all attributes private.

type Hour struct {

hour time.Time

availability Availability

}

// ...

func NewAvailableHour(hour time.Time) (*Hour, error) {

if err := validateTime(hour); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &Hour{

hour: hour,

availability: Available,

}, nil

}

We should also ensure that we’re not breaking any rules inside our type.

Bad example:

h := hour.NewAvailableHour("13:00")

if h.HasTrainingScheduled() {

h.SetState(hour.Available)

} else {

return errors.New("unable to cancel training")

}

Good example:

func (h *Hour) CancelTraining() error {

if !h.HasTrainingScheduled() {

return ErrNoTrainingScheduled

}

h.availability = Available

return nil

}

// ...

h := hour.NewAvailableHour("13:00")

if err := h.CancelTraining(); err != nil {

return err

}

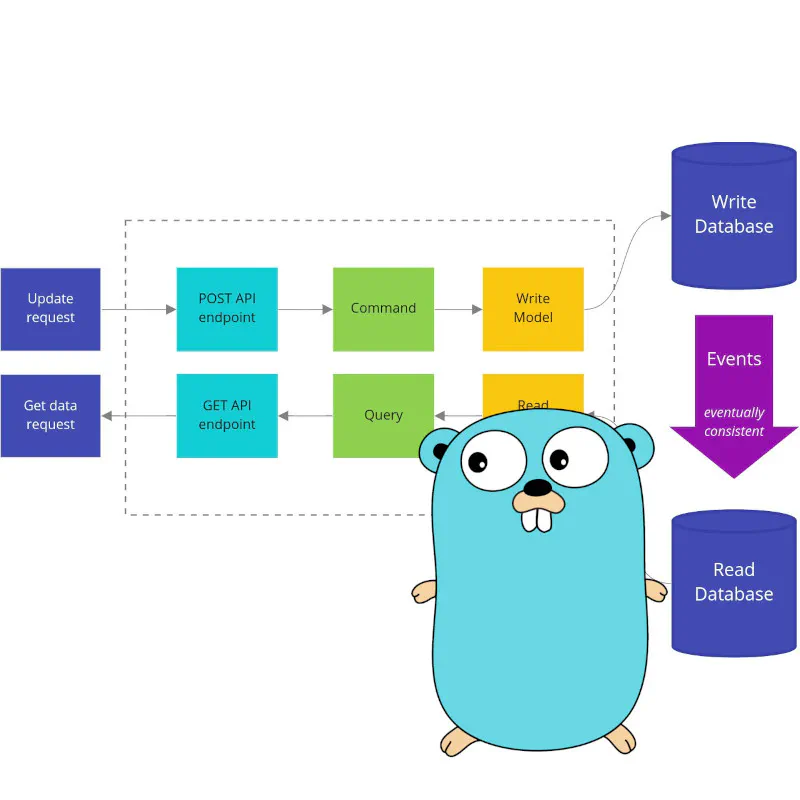

The Third Rule - domain needs to be database agnostic

There are multiple schools of thought here. Some say it’s fine to have the domain impacted by the database client. From our experience, keeping the domain strictly free of any database influence works best.

The most important reasons are:

- domain types are not shaped by the database solution used: they should be shaped only by business rules

- we can store data in the database in a more optimal way

- because of Go’s design and lack of “magic” like annotations, ORMs or any database solutions have an even more significant impact

Tip

Domain-First approach

If the project is complex enough, we can spend 2-4 weeks working on the domain layer with just an in-memory database implementation. In that case, we can explore the idea deeper and defer the decision about which database to choose. All our implementation is based on unit tests.

We’ve tried this approach several times, and it always worked nicely. It’s also a good idea to set a timebox here to avoid spending too much time.

Keep in mind that this approach requires a good relationship and a lot of trust from the business! If your relationship with business is far from good, Strategic DDD patterns will improve it. Been there, done that!

To keep this article from getting too long, let’s just introduce the Repository interface and assume that it works. 😉 I’ll cover this topic more in-depth in the next article.

type Repository interface {

GetOrCreateHour(ctx context.Context, time time.Time) (*Hour, error)

UpdateHour(

ctx context.Context,

hourTime time.Time,

updateFn func(h *Hour) (*Hour, error),

) error

}

Note

You may ask why `UpdateHour` has `updateFn func(h *Hour) (*Hour, error)`: we'll use that for handling transactions nicely. You can learn more in the article about repositories.

Using domain objects

I did a small refactor of our gRPC endpoints to provide an API that is more “behavior-oriented” rather than CRUD. It better reflects the new characteristics of the domain. From my experience, it’s also much easier to maintain multiple small methods than one “god” method that allows us to update everything.

--- a/api/protobuf/trainer.proto

+++ b/api/protobuf/trainer.proto

@@ -6,7 +6,9 @@ import "google/protobuf/timestamp.proto";

service TrainerService {

rpc IsHourAvailable(IsHourAvailableRequest) returns (IsHourAvailableResponse) {}

- rpc UpdateHour(UpdateHourRequest) returns (EmptyResponse) {}

+ rpc ScheduleTraining(UpdateHourRequest) returns (EmptyResponse) {}

+ rpc CancelTraining(UpdateHourRequest) returns (EmptyResponse) {}

+ rpc MakeHourAvailable(UpdateHourRequest) returns (EmptyResponse) {}

}

message IsHourAvailableRequest {

@@ -19,9 +21,6 @@ message IsHourAvailableResponse {

message UpdateHourRequest {

google.protobuf.Timestamp time = 1;

-

- bool has_training_scheduled = 2;

- bool available = 3;

}

message EmptyResponse {}

The implementation is now much simpler and easier to understand. We also have no logic here: just some orchestration. Our gRPC handler now has 18 lines and no domain logic!

func (g GrpcServer) MakeHourAvailable(ctx context.Context, request *trainer.UpdateHourRequest) (*trainer.EmptyResponse, error) {

trainingTime, err := protoTimestampToTime(request.Time)

if err != nil {

return nil, status.Error(codes.InvalidArgument, "unable to parse time")

}

if err := g.hourRepository.UpdateHour(ctx, trainingTime, func(h *hour.Hour) (*hour.Hour, error) {

if err := h.MakeAvailable(); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return h, nil

}); err != nil {

return nil, status.Error(codes.Internal, err.Error())

}

return &trainer.EmptyResponse{}, nil

}

Tip

No more Eight-thousanders

As I remember from the old times, many Eight-thousanders were actually HTTP controllers with a lot of domain logic.

By hiding complexity inside our domain types and keeping the rules I described, we can prevent uncontrolled growth here.

That’s all for today

I don’t want to make this article too long. Let’s go step by step!

If you can’t wait, the entire working diff for the refactor is available on GitHub. In the next article, I’ll cover one part of the diff that isn’t explained here: repositories.

Even though it’s still the beginning, some simplifications in our code are already visible.

The current implementation of the model is also not perfect: that’s good! You’ll never implement the perfect model from the beginning. It’s better to be prepared to change this model easily than to waste time trying to make it perfect. After I added tests for the model and separated it from the rest of the application, I can change it without any fear.

Can I already put that I know DDD to my CV?

Not yet.

I needed 3 years after I heard about DDD to connect all the dots (this was before I heard about Go). 😉 After that, I saw why all the techniques we’ll describe in the next articles are so important. But connecting the dots requires some patience and trust that it will work. It’s worth it! You won’t need 3 years like me, but we’ve currently planned about 10 articles on both strategic and tactical patterns. 😉 There are still a lot of new features and parts to refactor in Wild Workouts!

I know that nowadays many people promise you can become an expert in some area after 10 minutes with an article or video. The world would be beautiful if that were possible, but in reality, it’s not that simple.

Fortunately, a big part of the knowledge we share is universal and can be applied to multiple technologies, not only Go. You can treat these learnings as an investment in your career and mental health in the long term. 😉 There’s nothing better than solving the right problems without fighting unmaintainable code!

What is your experience with DDD in Go? Was it good or bad? Was it different from how we’re doing it? Do you think DDD might be useful in your project? Please let us know in the comments!

Do you have any colleagues who might be interested in this topic? Please share this article with them! Even if they don’t work in Go. 😉