When to avoid DRY in Go

In this post, we begin refactoring Wild Workouts. Previous articles will give you more context, but reading them isn’t necessary to understand this one.

Background story

Meet Susan, a software engineer bored at her current job working with legacy enterprise software. Susan started looking for a new gig and found the Wild Workouts startup, which uses serverless Go microservices. This seemed fresh and modern, so after a smooth hiring process, she started her first day at the company.

There were just a few engineers on the team, so Susan’s onboarding was blazing fast. On her first day, she was assigned a task meant to make her familiar with the application.

We need to store each user’s last IP address. This will enable new security features in the future, like extra confirmation when logging in from a new location. For now, we just want to keep it in the database.

Susan explored the application for a while, trying to understand what was happening in each service and where to add a new field for the IP address. Finally, she discovered a User structure that she could extend.

// User defines model for User.

type User struct {

Balance int `json:"balance"`

DisplayName string `json:"displayName"`

Role string `json:"role"`

+ LastIp string `json:"lastIp"`

}

It didn’t take Susan long to post her first pull request. Soon, Dave, a senior engineer, added a comment during code review.

I don’t think we’re supposed to expose this field via the REST API.

Susan was surprised since she was sure she’d updated the database model. Confused, she asked Dave if this was the correct place to add a new field.

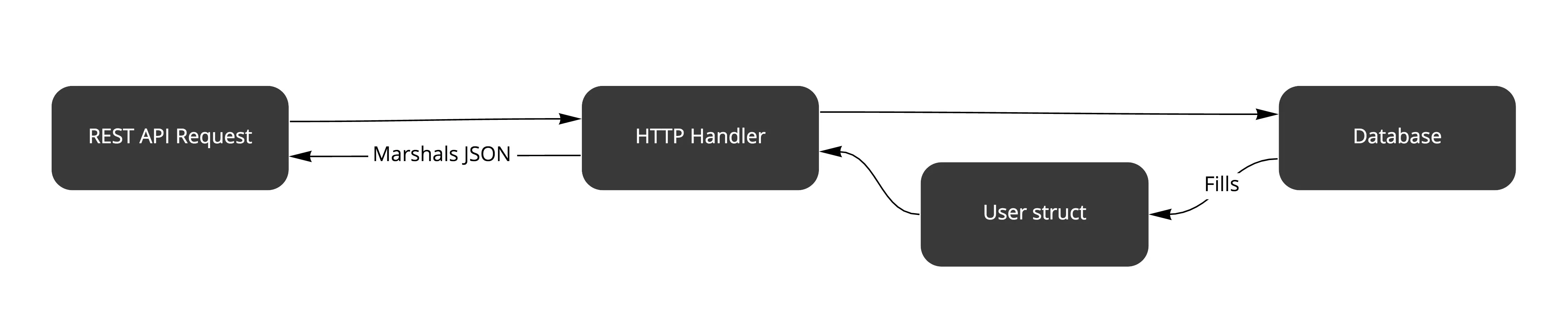

Dave explained that Firestore, the application’s database, stores documents marshaled from Go structures. So the User struct is compatible with both frontend responses and storage.

“Thanks to this approach, you don’t need to duplicate the code. It’s enough to change the YAML definition once and regenerate the file”, he said enthusiastically.

Grateful for the tip, Susan added one more change to hide the new field from the API response.

diff --git a/internal/users/http.go b/internal/users/http.go

index 9022e5d..cd8fbdc 100644

--- a/internal/users/http.go

+++ b/internal/users/http.go

@@ -27,5 +30,8 @@ func (h HttpServer) GetCurrentUser(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

user.Role = authUser.Role

user.DisplayName = authUser.DisplayName

+ // Don't expose the user's last IP externally

+ user.LastIp = nil

+

render.Respond(w, r, user)

}

One line was enough to fix this issue. That was quite a productive first day for Susan.

Second thoughts

Even though Susan’s solution was approved and merged, something bothered her on her commute home. Is it the right approach to keep the same struct for both API response and database model? Don’t we risk accidentally exposing users’ private details if we keep extending it as the application grows? What if we want to change only the API response without changing the database fields?

What about splitting the two structures? That’s what Susan would do at her old job, but maybe these were enterprise patterns that should not be used in a Go microservice. Also, the team seemed very rigorous about the Don’t Repeat Yourself principle.

Refactoring

The next day, Susan explained her doubts to Dave and asked for his opinion. At first, he didn’t understand the concern and mentioned that maybe she needed to get used to the “Go way” of doing things.

Susan pointed to another piece of code in Wild Workouts that used a similar ad hoc solution. She shared that, from her experience, such code can quickly get out of control.

user, err := h.db.GetUser(r.Context(), authUser.UUID)

if err != nil {

httperr.InternalError("cannot-get-user", err, w, r)

return

}

user.Role = authUser.Role

user.DisplayName = authUser.DisplayName

render.Respond(w, r, user)

Eventually, they agreed to discuss this again over a new PR. Susan prepared a refactoring proposal.

diff --git a/internal/users/firestore.go b/internal/users/firestore.go

index 7f3fca0..670bfaa 100644

--- a/internal/users/firestore.go

+++ b/internal/users/firestore.go

@@ -9,6 +9,13 @@ import (

"google.golang.org/grpc/status"

)

+type UserModel struct {

+ Balance int

+ DisplayName string

+ Role string

+ LastIP string

+}

+

diff --git a/internal/users/http.go b/internal/users/http.go

index 9022e5d..372b5ca 100644

--- a/internal/users/http.go

+++ b/internal/users/http.go

@@ -1,6 +1,7 @@

- user.Role = authUser.Role

- user.DisplayName = authUser.DisplayName

- render.Respond(w, r, user)

+ userResponse := User{

+ DisplayName: authUser.DisplayName,

+ Balance: user.Balance,

+ Role: authUser.Role,

+ }

+

+ render.Respond(w, r, userResponse)

}

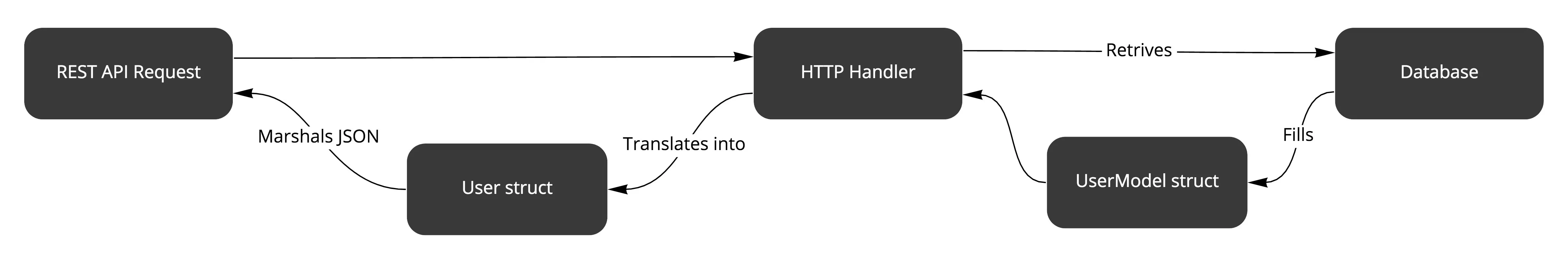

This time, Susan didn’t touch the OpenAPI definition. After all, she wasn’t supposed to change the REST API. Instead, she manually created another structure, just like User, but exclusive to the database model. Then she extended it with a new field.

The new solution is a bit longer in lines of code, but it removed coupling between the REST API and the database layer (all without introducing another microservice). The next time someone wants to add a field, they can do it by updating the proper structure.

The Clash of Principles

Dave’s biggest concern was that the second solution breaks the DRY principle and introduces boilerplate. On the other hand, Susan was afraid that the original approach violates the Single Responsibility Principle (the “S” in SOLID). Who’s right?

It’s tough to come up with strict rules. Sometimes code duplication seems like boilerplate, but it’s one of the best tools to fight code coupling. It helps to ask yourself if the code using the common structure is likely to change together. If not, it’s safe to assume duplication is the right choice.

Usually, DRY is better applied to behaviors, not data. For example, extracting common code to a separate function doesn’t have the downsides we’ve discussed.

What’s the big deal?

Is such a minor change even “architecture”?

Susan introduced a small change that had consequences she didn’t anticipate. It was obvious to other engineers, but not to a newcomer. I guess you also know the feeling of being afraid to make changes in an unknown system because you can’t predict what it might trigger.

If you make many wrong decisions, even small ones, they tend to compound. Eventually, developers start complaining that the application is hard to work with. The turning point is when someone mentions a “rewrite”, and suddenly you know you have a big problem.

The alternative to good design is always bad design. There is no such thing as no design.

It’s worth discussing architecture decisions before you run into issues. “No architecture” will just leave you with bad architecture.

Can microservices save you?

With all the benefits that microservices gave us, a dangerous idea also appeared, preached by some “how to build microservices” guides. It says that microservices will simplify your application. Because building large software projects is hard, some promise that you won’t need to worry about it if you split your application into tiny chunks.

This sounds good on paper, but it misses the point of splitting software. How do you know where to put the boundaries? Will you separate a service based on each database entity? REST endpoints? Features? How do you ensure low coupling between services?

The Distributed Monolith

If you start with poorly separated services, you’re likely to end up with the same monolith you tried to avoid, plus network overhead and complex tooling to manage the mess (also known as a distributed monolith). You’ll just replace highly coupled modules with highly coupled services. And because everyone runs a Kubernetes cluster now, you may even think you’re following industry standards.

Even if you can rewrite a single service in one afternoon, can you as quickly change how services communicate with each other? What if they’re owned by multiple teams, based on wrong boundaries? Consider how much simpler it is to refactor a single application.

None of this negates other benefits of microservices, like independent deployments (crucial for Continuous Delivery) and easier horizontal scaling. As with all patterns, make sure you use the right tool for the job at the right time.

Note

We introduced similar issues on purpose in Wild Workouts. We will look into this in future posts and discuss other splitting techniques.

You can find some of the ideas in Robert’s post: Why using Microservices or Monolith can be just a detail?.

Does this all apply to Go?

Open-source Go projects are usually low-level applications and infrastructure tools. This was especially true in the early days, and it’s still hard to find good examples of Go applications that handle domain logic.

By “domain logic,” I don’t mean financial applications or complex business software. If you develop any kind of web application, there’s a good chance you have some complex domain cases you need to model somehow.

Following some DDD examples can make you feel like you’re no longer writing Go. I’m well aware that forcing OOP patterns straight from Java is not fun to work with. However, some language-agnostic ideas are worth considering.

What’s the alternative?

We spent the last few years exploring this topic. We love the simplicity of Go, but we’ve also had success with ideas from Domain-Driven Design and Clean Architecture.

For some reason, developers didn’t stop talking about technical debt and legacy software with the arrival of microservices. Instead of looking for a silver bullet, we prefer to use business-oriented patterns together with microservices in a pragmatic way.

We’re not done refactoring Wild Workouts yet. In one of the following posts, we’ll see how to introduce Clean Architecture to the project.