Combining DDD, CQRS, and Clean Architecture in Go

Why should I care?

Working on a programming project is similar to planning and building a residential district. If you know the district will expand in the near future, you need to keep space for future improvements. Even if at the beginning it may look like a waste of space. You should reserve room for future facilities like residential blocks, hospitals, and temples. Without that, you will be forced to destroy buildings and streets to make space for new ones. It’s much better to think about that earlier.

The situation is the same with code. If you know the project will be developed for longer than one month, you should keep the long term in mind from the beginning. You need to write your code in a way that won’t block your future work. Even if at the beginning it may look like over-engineering and a lot of extra boilerplate, you need to keep the long term in mind.

This doesn’t mean you need to plan every feature you will implement in the future – it’s actually the opposite. This approach helps you adapt to new requirements or a changing understanding of your domain. Big upfront design is not needed here. This is critical in current times, when the world is changing fast and those who can’t adapt can simply go out of business.

This is exactly what these patterns give you when combined: the ability to maintain constant development speed. Without destroying or touching existing code too much.

Does it require more thinking and planning? Is it a more challenging way? Do you need to have extra knowledge to do that? Sure! But the long term result is worth that! Fortunately, you are in the right place to learn that. 😉

But let’s leave the theory behind us. Let’s get to the code. In this article, we will skip the reasoning for our design choices. We described these already in the previous articles. If you haven’t read them yet, I recommend doing so – you will understand this article better.

As in previous articles, we will base our code on refactoring a real open-source project. This should make the examples more realistic and applicable to your own projects.

Are you ready?

Note

This is not just another article with random code snippets.

This post is part of a bigger series where we show how to build Go applications that are easy to develop, maintain, and fun to work with in the long term. We are doing it by sharing proven techniques based on many experiments we did with teams we lead and scientific research.

You can learn these patterns by building with us a fully functional example Go web application – Wild Workouts.

We did one thing differently – we included some subtle issues to the initial Wild Workouts implementation. Have we lost our minds to do that? Not yet. 😉 These issues are common for many Go projects. In the long term, these small issues become critical and stop adding new features.

It’s one of the essential skills of a senior or lead developer; you always need to keep long-term implications in mind.

We will fix them by refactoring Wild Workouts. In that way, you will quickly understand the techniques we share.

Do you know that feeling after reading an article about some technique and trying implement it only to be blocked by some issues skipped in the guide? Cutting these details makes articles shorter and increases page views, but this is not our goal. Our goal is to create content that provides enough know-how to apply presented techniques. If you did not read previous articles from the series yet, we highly recommend doing that.

We believe that in some areas, there are no shortcuts. If you want to build complex applications in a fast and efficient way, you need to spend some time learning that. If it was simple, we wouldn’t have large amounts of scary legacy code.

Here’s the full list of 14 articles released so far.

The full source code of Wild Workouts is available on GitHub. Don’t forget to leave a star for our project! ⭐

Let’s refactor

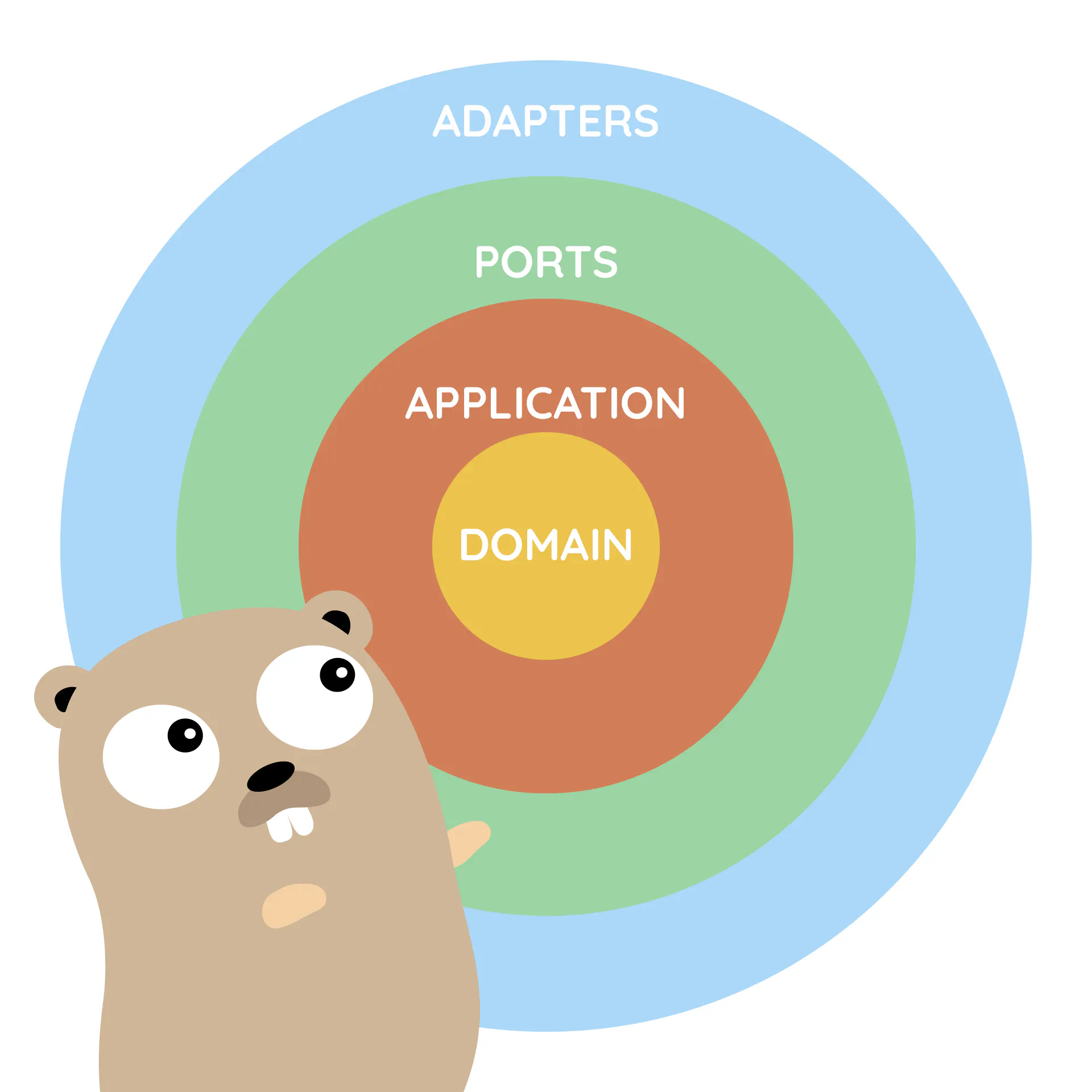

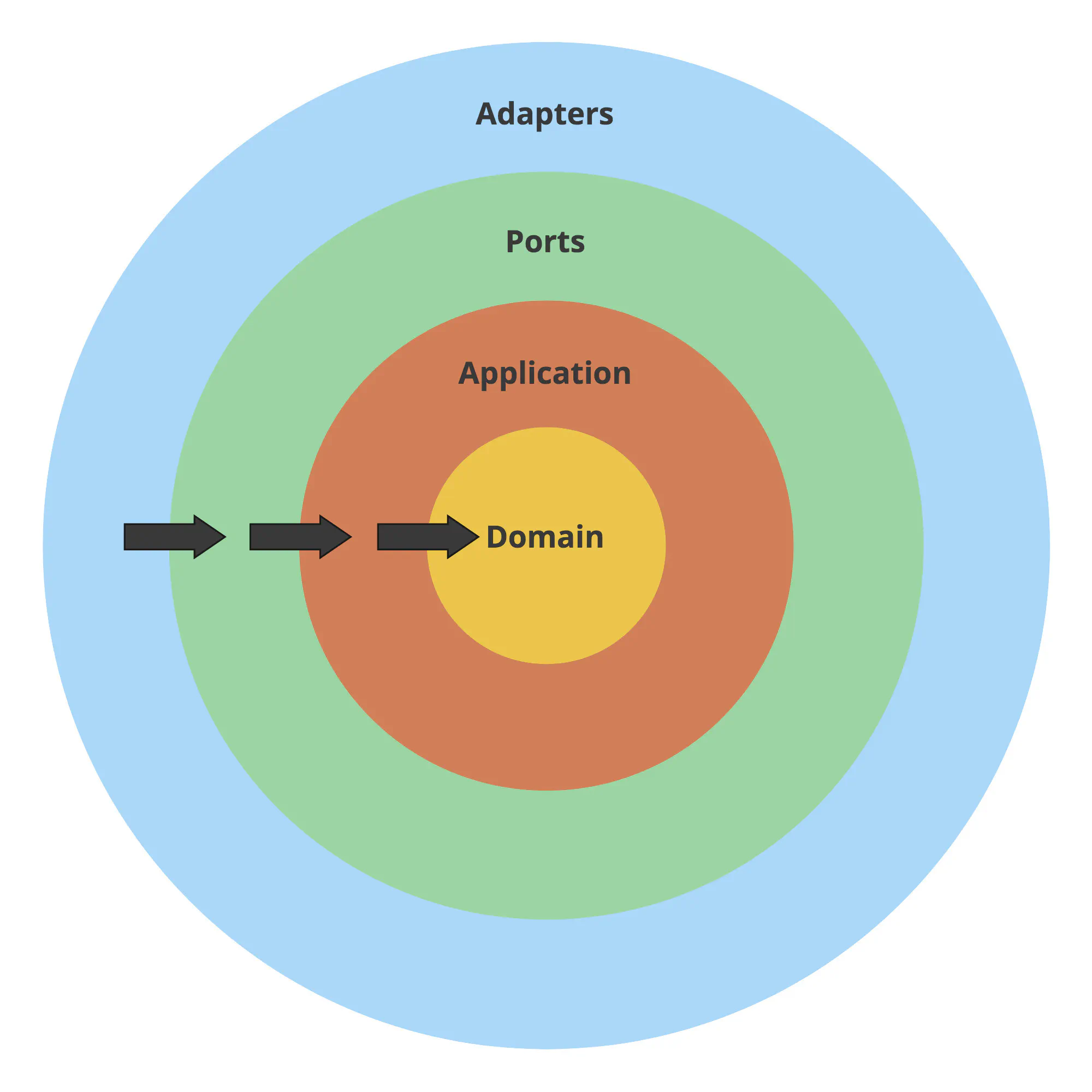

Let’s start our refactoring with the Domain-First approach. We will begin by introducing a domain layer. This ensures that implementation details do not affect our domain code. We can also put all our efforts into understanding the business problem, not writing boring database queries and API endpoints.

The Domain-First approach works well for both rescue (refactoring 😉) and greenfield projects.

To start building my domain layer, I needed to identify what the application is actually doing.

This article will focus on refactoring of trainings Wild Workouts microservice.

I started with identifying use cases handled by the application.

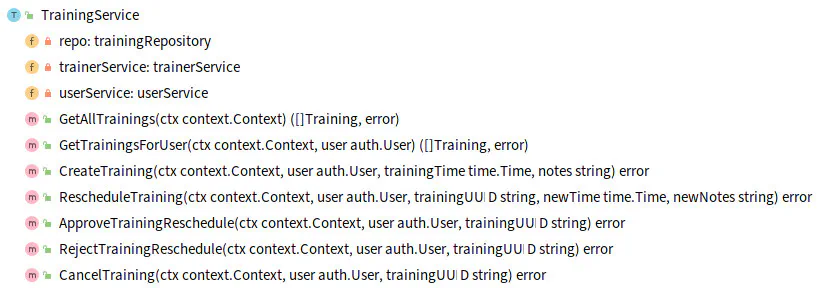

After previous refactoring to Clean Architecture, we can find it in the TrainingService.

When I work with a messy application, I look at RPC and HTTP endpoints to find supported use cases.

One of the functionalities I identified is the approval of training reschedule. In Wild Workouts, a training reschedule approval is required if it was requested less than 24 hours before its date. If an attendee requests a reschedule, the trainer needs to approve it. If a trainer requests a reschedule, the attendee needs to accept it.

- func (c TrainingService) ApproveTrainingReschedule(ctx context.Context, user auth.User, trainingUUID string) error {

- return c.repo.ApproveTrainingReschedule(ctx, trainingUUID, func(training Training) (Training, error) {

- if training.ProposedTime == nil {

- return Training{}, errors.New("training has no proposed time")

- }

- if training.MoveProposedBy == nil {

- return Training{}, errors.New("training has no MoveProposedBy")

- }

- if *training.MoveProposedBy == "trainer" && training.UserUUID != user.UUID {

- return Training{}, errors.Errorf("user '%s' cannot approve reschedule of user '%s'", user.UUID, training.UserUUID)

- }

- if *training.MoveProposedBy == user.Role {

- return Training{}, errors.New("reschedule cannot be accepted by requesting person")

- }

-

- training.Time = *training.ProposedTime

- training.ProposedTime = nil

-

- return training, nil

- })

- }

Start with the domain

Even if this doesn’t look like the worst code you’ve ever seen, functions like ApproveTrainingReschedule tend to get more complex over time.

More complex functions mean more potential bugs during future development.

This is even more likely if you are new to the project and lack the “shaman knowledge” about it. You should always consider all the people who will work on the project after you, and make it resistant to being accidentally broken by them. That will help your project avoid becoming the legacy code that everybody is afraid to touch. You probably know that feeling when you’re new to a project and afraid to touch anything for fear of breaking the system.

It’s not uncommon for people to change jobs more often than every two years. This makes it even more critical for long-term project development.

If you don’t believe this code may become complex, I recommend checking the Git history of the worst place in the project you work on. In most cases, that worst code started with “just a couple of simple ifs”. 😉 The more complex the code becomes, the more difficult it will be to simplify later. We should be sensitive to emerging complexity and try to simplify it as soon as we can.

Training domain entity

While analyzing the current use cases handled by the trainings microservice, I found that they are all related to a training.

It’s natural to create a Training type to handle these operations.

Note

noun == entity

Is this a valid approach for discovering entities? Well, not really.

DDD provides tools that help us model complex domains without guessing (Strategic DDD Patterns, Aggregates). We don’t want to guess what our aggregates look like – we want tools to discover them. The Event Storming technique is extremely useful here… but that’s a topic for an entire separate article.

The topic is complex enough to deserve a couple of articles. And that’s what we will do shortly. 😉

Does this mean you shouldn’t use these techniques without Strategic DDD Patterns? Of course not! The current approach can be good enough for simpler projects. Unfortunately (or fortunately 😉), not all projects are simple.

package training

// ...

type Training struct {

uuid string

userUUID string

userName string

time time.Time

notes string

proposedNewTime time.Time

moveProposedBy UserType

canceled bool

}

All fields are private to provide encapsulation. This is critical to meet the “always keep a valid state in the memory” rule from the article about DDD Lite.

Thanks to validation in the constructor and encapsulated fields, we are sure that Training is always valid.

Now, someone who has no knowledge about the project cannot use it in the wrong way.

The same rule applies to any methods provided by Training.

package training

func NewTraining(uuid string, userUUID string, userName string, trainingTime time.Time) (*Training, error) {

if uuid == "" {

return nil, errors.New("empty training uuid")

}

if userUUID == "" {

return nil, errors.New("empty userUUID")

}

if userName == "" {

return nil, errors.New("empty userName")

}

if trainingTime.IsZero() {

return nil, errors.New("zero training time")

}

return &Training{

uuid: uuid,

userUUID: userUUID,

userName: userName,

time: trainingTime,

}, nil

}

Approve reschedule in the domain layer

As described in DDD Lite introduction, we build our domain with methods oriented on behaviours.

Not on data.

Let’s model ApproveReschedule on our domain entity.

package training

// ...s

func (t *Training) IsRescheduleProposed() bool {

return !t.moveProposedBy.IsZero() && !t.proposedNewTime.IsZero()

}

var ErrNoRescheduleRequested = errors.New("no training reschedule was requested yet")

func (t *Training) ApproveReschedule(userType UserType) error {

if !t.IsRescheduleProposed() {

return errors.WithStack(ErrNoRescheduleRequested)

}

if t.moveProposedBy == userType {

return errors.Errorf(

"trying to approve reschedule by the same user type which proposed reschedule (%s)",

userType.String(),

)

}

t.time = t.proposedNewTime

t.proposedNewTime = time.Time{}

t.moveProposedBy = UserType{}

return nil

}

If you haven’t had the chance to read:

I highly recommend checking them out. They will help you understand this article better. They explain the decisions and techniques we combine in this article.

Orchestrate with command

Now the application layer can be responsible only for the orchestration of the flow. There is no domain logic there. We hide the entire business complexity in the domain layer. This was exactly our goal.

For getting and saving a training, we use the Repository pattern.

package command

// ...

func (h ApproveTrainingRescheduleHandler) Handle(ctx context.Context, cmd ApproveTrainingReschedule) (err error) {

defer func() {

logs.LogCommandExecution("ApproveTrainingReschedule", cmd, err)

}()

return h.repo.UpdateTraining(

ctx,

cmd.TrainingUUID,

cmd.User,

func(ctx context.Context, tr *training.Training) (*training.Training, error) {

originalTrainingTime := tr.Time()

if err := tr.ApproveReschedule(cmd.User.Type()); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

err := h.trainerService.MoveTraining(ctx, tr.Time(), originalTrainingTime)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return tr, nil

},

)

}

Refactoring of training cancelation

Let’s now take a look at CancelTraining from TrainingService.

The domain logic is simple: you can cancel a training up to 24 hours before its date. If it’s less than 24 hours before the training and you want to cancel it anyway:

- if you are the trainer, the attendee will get their training “back” plus one extra session (nobody likes to change plans on the same day!)

- if you are the attendee, you will lose this training

This is how the current implementation looks like:

- func (c TrainingService) CancelTraining(ctx context.Context, user auth.User, trainingUUID string) error {

- return c.repo.CancelTraining(ctx, trainingUUID, func(training Training) error {

- if user.Role != "trainer" && training.UserUUID != user.UUID {

- return errors.Errorf("user '%s' is trying to cancel training of user '%s'", user.UUID, training.UserUUID)

- }

-

- var trainingBalanceDelta int

- if training.CanBeCancelled() {

- // just give training back

- trainingBalanceDelta = 1

- } else {

- if user.Role == "trainer" {

- // 1 for cancelled training +1 fine for cancelling by trainer less than 24h before training

- trainingBalanceDelta = 2

- } else {

- // fine for cancelling less than 24h before training

- trainingBalanceDelta = 0

- }

- }

-

- if trainingBalanceDelta != 0 {

- err := c.userService.UpdateTrainingBalance(ctx, training.UserUUID, trainingBalanceDelta)

- if err != nil {

- return errors.Wrap(err, "unable to change trainings balance")

- }

- }

-

- err := c.trainerService.CancelTraining(ctx, training.Time)

- if err != nil {

- return errors.Wrap(err, "unable to cancel training")

- }

-

- return nil

- })

- }

You can see some kind of “algorithm” for calculating the training balance delta during cancellation. That’s not a good sign in the application layer.

Logic like this one should live in our domain layer.

If you start to see some if’s related to logic in your application layer, you should think about how to move it to the domain layer.

It will be easier to test and re-use in other places.

It may depend on the project, but often domain logic is fairly stable after initial development and can live unchanged for a long time. It can survive moving between services, framework changes, library changes, and API changes. Thanks to this separation, we can make all these changes in a much safer and faster way.

Let’s decompose the CancelTraining method to multiple, separated pieces.

That will allow us to test and change them independently.

First, we need to handle cancellation logic and marking Training as canceled.

package training

func (t Training) CanBeCanceledForFree() bool {

return t.time.Sub(time.Now()) >= time.Hour*24

}

var ErrTrainingAlreadyCanceled = errors.New("training is already canceled")

func (t *Training) Cancel() error {

if t.IsCanceled() {

return ErrTrainingAlreadyCanceled

}

t.canceled = true

return nil

}

Nothing really complicated here. That’s good!

The second part that needs to move is the “algorithm” for calculating the trainings balance after cancellation.

In theory, we could put it in the Cancel() method, but in my opinion it would break the Single Responsibility Principle and CQS.

And I like small functions.

But where should we put it? Some object? A domain service? In some languages, like the one that starts with J and ends with ava, that would make sense. But in Go, it’s good enough to just create a simple function.

package training

// CancelBalanceDelta return trainings balance delta that should be adjusted after training cancelation.

func CancelBalanceDelta(tr Training, cancelingUserType UserType) int {

if tr.CanBeCanceledForFree() {

// just give training back

return 1

}

switch cancelingUserType {

case Trainer:

// 1 for cancelled training +1 "fine" for cancelling by trainer less than 24h before training

return 2

case Attendee:

// "fine" for cancelling less than 24h before training

return 0

default:

panic(fmt.Sprintf("not supported user type %s", cancelingUserType))

}

}

The code is now straightforward. I can imagine that I could sit with any non-technical person and go through this code to explain how it works.

What about tests? It may be a bit controversial, but in my opinion tests are redundant here. Test code would replicate the implementation of the function. Any change in the calculation algorithm would require copying the logic to the tests. I wouldn’t write a test here, but if you’ll sleep better at night – why not!

Moving CancelTraining to command

Our domain is ready, so let’s now use it. We will do it in the same way as previously:

- getting the entity from the repository,

- orchestration of domain stuff,

- calling external

trainerservice to cancel the training (this service is the point of truth of “trainer’s calendar”), - returning entity to be saved in the database.

package command

// ...

func (h CancelTrainingHandler) Handle(ctx context.Context, cmd CancelTraining) (err error) {

defer func() {

logs.LogCommandExecution("CancelTrainingHandler", cmd, err)

}()

return h.repo.UpdateTraining(

ctx,

cmd.TrainingUUID,

cmd.User,

func(ctx context.Context, tr *training.Training) (*training.Training, error) {

if err := tr.Cancel(); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if balanceDelta := training.CancelBalanceDelta(*tr, cmd.User.Type()); balanceDelta != 0 {

err := h.userService.UpdateTrainingBalance(ctx, tr.UserUUID(), balanceDelta)

if err != nil {

return nil, errors.Wrap(err, "unable to change trainings balance")

}

}

if err := h.trainerService.CancelTraining(ctx, tr.Time()); err != nil {

return nil, errors.Wrap(err, "unable to cancel training")

}

return tr, nil

},

)

}

Repository refactoring

The initial implementation of the repository was pretty tricky because of the custom method for every use case.

- type trainingRepository interface {

- FindTrainingsForUser(ctx context.Context, user auth.User) ([]Training, error)

- AllTrainings(ctx context.Context) ([]Training, error)

- CreateTraining(ctx context.Context, training Training, createFn func() error) error

- CancelTraining(ctx context.Context, trainingUUID string, deleteFn func(Training) error) error

- RescheduleTraining(ctx context.Context, trainingUUID string, newTime time.Time, updateFn func(Training) (Training, error)) error

- ApproveTrainingReschedule(ctx context.Context, trainingUUID string, updateFn func(Training) (Training, error)) error

- RejectTrainingReschedule(ctx context.Context, trainingUUID string, updateFn func(Training) (Training, error)) error

- }

Thanks to introducing the training.Training entity, we can have a much simpler version: one method for adding a new training and one for updating.

package training

// ...

type Repository interface {

AddTraining(ctx context.Context, tr *Training) error

GetTraining(ctx context.Context, trainingUUID string, user User) (*Training, error)

UpdateTraining(

ctx context.Context,

trainingUUID string,

user User,

updateFn func(ctx context.Context, tr *Training) (*Training, error),

) error

}

As in the previous article, we implemented our repository using Firestore. We will also use Firestore in the current implementation. Keep in mind that this is an implementation detail – you can use any database you want. In the previous article, we showed example implementations using different databases.

package adapters

// ...

func (r TrainingsFirestoreRepository) UpdateTraining(

ctx context.Context,

trainingUUID string,

user training.User,

updateFn func(ctx context.Context, tr *training.Training) (*training.Training, error),

) error {

trainingsCollection := r.trainingsCollection()

return r.firestoreClient.RunTransaction(ctx, func(ctx context.Context, tx *firestore.Transaction) error {

documentRef := trainingsCollection.Doc(trainingUUID)

firestoreTraining, err := tx.Get(documentRef)

if err != nil {

return errors.Wrap(err, "unable to get actual docs")

}

tr, err := r.unmarshalTraining(firestoreTraining)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if err := training.CanUserSeeTraining(user, *tr); err != nil {

return err

}

updatedTraining, err := updateFn(ctx, tr)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return tx.Set(documentRef, r.marshalTraining(updatedTraining))

})

}

Connecting everything

How do we use our code now? What about our ports layer? Thanks to the refactoring that Miłosz did in refactoring to Clean Architecture article, our ports layer is decoupled from other layers. That’s why, after this refactoring, it requires almost no significant changes. We just call the application command instead of the application service.

package ports

// ...

type HttpServer struct {

app app.Application

}

// ...

func (h HttpServer) CancelTraining(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

trainingUUID := r.Context().Value("trainingUUID").(string)

user, err := newDomainUserFromAuthUser(r.Context())

if err != nil {

httperr.RespondWithSlugError(err, w, r)

return

}

err = h.app.Commands.CancelTraining.Handle(r.Context(), command.CancelTraining{

TrainingUUID: trainingUUID,

User: user,

})

if err != nil {

httperr.RespondWithSlugError(err, w, r)

return

}

}

How to approach such refactoring in a real project?

It may not be obvious how to do such a refactoring in a real project. It’s hard to do a code review and agree as a team on the refactoring direction.

In my experience, the best approach is Pair or Mob programming. Even if at the beginning you may feel it’s a waste of time, the knowledge sharing and instant review will save a lot of time in the future. Thanks to great knowledge sharing, you can work much faster after the initial project or refactoring phase.

In this case, don’t consider the time “lost” for Mob/Pair programming. Consider the time you may lose by not doing it. It will also help you finish the refactoring much faster because you won’t need to wait for decisions. You can agree on them immediately.

Mob and pair programming also work perfectly when implementing complex, greenfield projects. Knowledge sharing is an especially important investment in that case. I’ve seen multiple times how this approach allowed teams to move very fast on the project in the long term.

When you are doing refactoring, it’s also critical to agree on reasonable timeboxes. And keep them. You can quickly lose your stakeholders’ trust when you spend an entire month on refactoring and the improvement is not visible. It’s also critical to integrate and deploy your refactoring as fast as you can. Ideally, on a daily basis (if you can do it for non-refactoring work, I’m sure you can do it for refactoring as well!). If your changes stay unmerged and undeployed for a longer time, you increase the chance of breaking functionality. It will also block any work in the refactored service or make changes harder to merge (it’s not always possible to stop all other development around).

But how do you know if the project is complex enough to use mob programming? Unfortunately, there is no magic formula for that. But there are questions you should ask yourself:

- do we understand the domain?

- do we know how to implement that?

- will it end up with a monstrous pull request that nobody will be able to review?

- can we risk worse knowledge sharing while not doing mob/pair programming?

Summary

And we come to an end. 😄

The entire diff for the refactoring is available on our Wild Workouts GitHub (watch out, it’s huge!).

If you haven’t had the chance to read previous articles yet, you know what to do! Even if some of the approaches used are simplified, you should already be able to use them in your project and see value from them.I hope that after this article, you also see how all the introduced patterns work nicely together. If not yet, don’t worry. It took me three years to connect all the dots. But it was worth the time spent. After I understood how everything is connected, I started to look at new projects in a totally different way. It allowed me and my teams to work more efficiently in the long term.

It’s also important to mention that, like all techniques, this combination is not a silver bullet.

If you are creating a project that is not complex and won’t be touched any time soon after one month of development, it’s probably enough to put everything in one main package. 😉

Just keep in mind when that one month of development becomes one year!

We will also continue these topics in the next articles. We will shortly drift to Strategic DDD Patterns, which should also help you gain a higher-level perspective on your projects.

Did this article help you understand how to connect DDD, Clean Architecture, and CQRS? Is something still unclear? Please let us know in the comments! We’re happy to discuss all your questions!